Dr Saad Saleem Arif

Introduction

This study investigates the story of humans

from early hominid origins to the so-called “Human Era.” It

posits that modern humans, i.e. Prophet Adam’s descendants,

merged with or supplanted other contemporaneous anatomically

similar human populations. This hypothesis is supported by an

interdisciplinary approach that includes religious texts, such

as the Bible and the Quran, alongside scientific disciplines.

The paper presents diverse findings to construct a coherent

narrative on transitioning from hominids to modern humans.

The Emergence of Early Modern Humans

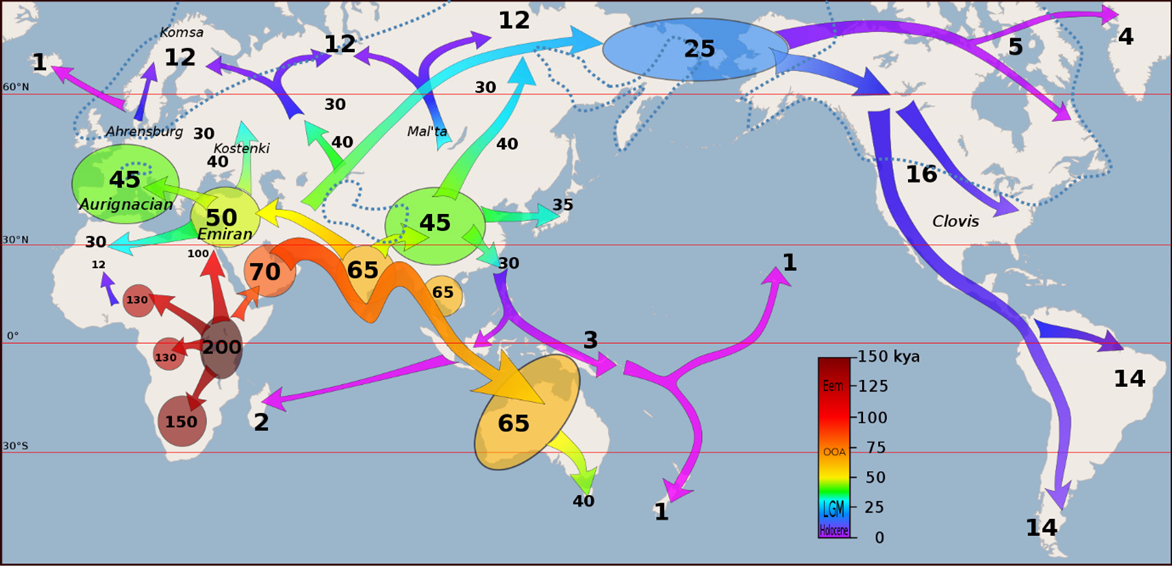

Fossil evidence indicates that anatomically

modern humans (Homo sapiens) first appeared in Africa around

200,000 to 300,000 years ago. Over time, these early humans

migrated globally, developing tools and surviving in various

environments (see Figure 1). For instance, humans left Africa

about 70,000 years ago and reached Central Asia around 40,000

years ago (Higham et al., 2014).

Figure 1: Migration of humans - when did

humans arrive first at any given place on Earth (scale for

time is in thousands of years)

Coexistence of Early Modern Humans with

Other Hominid Species

Early modern humans coexisted with other

hominid species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, for

thousands of years. Archaeological evidence shows these groups

interacted, competed, and interbred, contributing to modern

human genetic diversity (Prüfer et al., 2014). Neanderthals

and Denisovans disappeared from the fossil record around

40,000 years ago, likely due to competition with early modern

humans and environmental changes.

Cultural Characteristics of Early Modern

Humans

Anatomically akin to present-day humans,

early modern humans demonstrated characteristics that are

fundamental to our natural instincts and behaviours today:

● Communications Skills. Historical

records and archaeological findings suggest complex

communication abilities, such as symbolic cave paintings at

sites like Lascaux (France) and Altamira (Spain).

● Propensity to violence. Evidence

of skeletal trauma and weapon-inflicted injuries reveals early

humans' capacity for violence, likely related to conflicts

over resources or territory (Walker, 2001).

● Clothing and tools. Genetic

studies on lice suggest clothing was adopted around 170,000

years ago, coinciding with human migration patterns (Toups et

al., 2011). The use of clothes for protection and social

purposes in the Palaeolithic era is evidenced by the discovery

of bone tools believed to have been used for making clothing

(Gilligan, 2010). Levalloisian stone-flaking technique for

producing stone tools demonstrates a sophisticated

understanding of geometry.

● Burial rituals. Intentional

burials with grave goods suggest that early humans practised

rituals (Pearson, 1999).

● Diet. Stable isotope analysis

indicates a diet primarily composed of meat from large

ruminants, with mammoths being a significant prey species

(Richards & Trinkaus, 2019) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Relative proportions (in %) of

different prey species to the protein intake calculations

based on δ13C and δ15N isotope analysis from two sites. Taken

from (Richards & Trinkaus, 2019)

Commencement of the ‘Human Era’

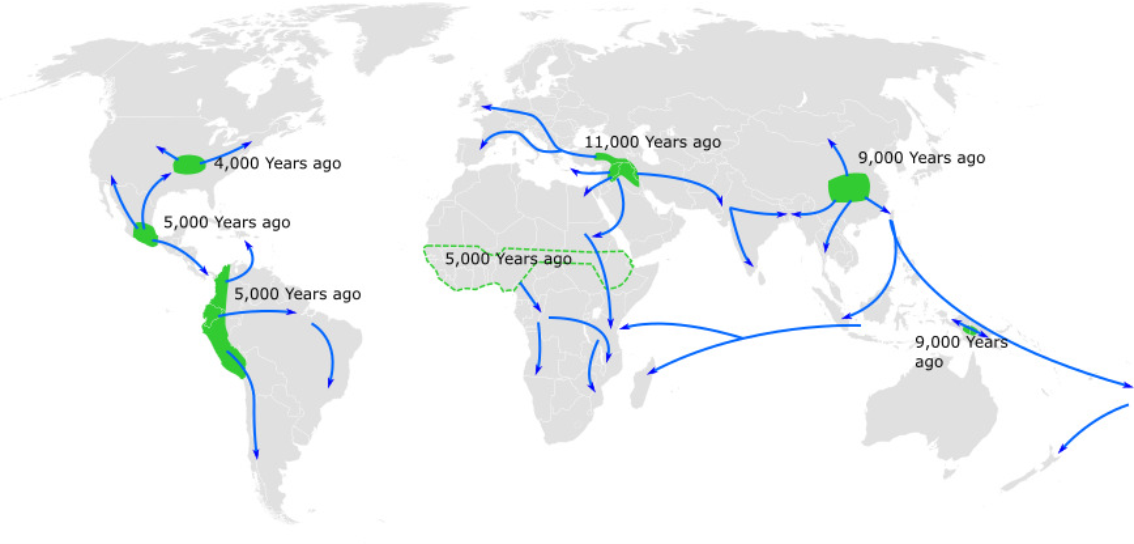

About 12,000 years ago, the agricultural

revolution began, fundamentally altering human society. With

the advent of farming, humans developed stable communities,

culminating in the first known cities. The city of Jericho is

often considered the first known city, built around 9,000 BCE

in the Levant region and Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey is

regarded as one of the earliest urban settlements, existing

from approximately 7100 BC to 5700 BC (Meece, 2006). Around

12,000 years ago, this period corresponded with the religious

narratives of Adam, who was considered the first true human

whose descendants developed agriculture and animal farming

(Genesis 4:2).

This alignment is also indicated in Surah

Baqarah of the Quran. God elevated humans to the status of “Khalifa,”

or stewards of Earth (Quran 2:30). Angels questioned this

promotion, referencing humans' tendency towards mischief and

bloodshed, an observation possible only if humans had already

existed on Earth before Prophet Adam. In summary, Prophet

Adam’s arrival signifies the handing over of the world’s

stewardship to Adam’s progeny. This promotion resulted in the

sudden employment of various technologies and humans’

extensive exploitation of the earth’s resources around 12,000

years ago.

This new era for humans is also called the

Human Era or the Holocene Era, and it started with the

Neolithic Revolution.

Prophet Adam’s Descendants and Other Humans

There were anatomically similar human

beings

before Prophet Adam, and he probably coexisted with them. The

survival of Prophet Adam's descendants can be attributed to

the spirit blown into Adam, as mentioned in the Qur’a#n 38:72

and the knowledge God gave to Adam and his progeny for

agriculture, animal farming, as mentioned in Genesis 4:2, and

a fully functional language. Other human populations may have

perished due to environmental changes, assimilated through

intermarriage with Prophet Adam’s progeny and some killed by

Prophet Adam’s progeny.

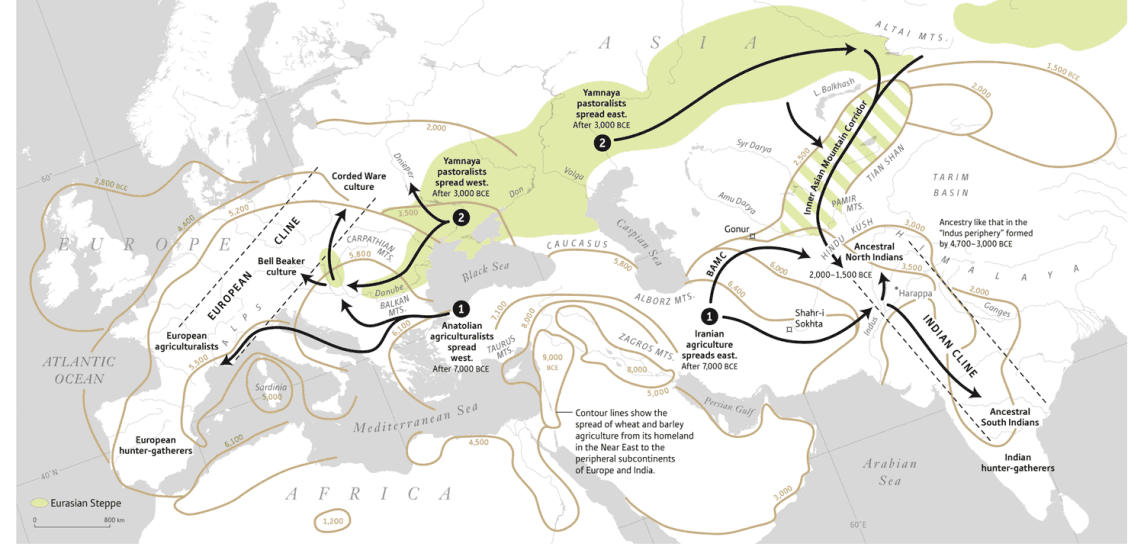

For example, Neolithic Europe experienced

significant genetic diversity changes due to population

replacements and expansions, primarily from the Levant. These

movements led to substantial genetic admixture with existing

European populations, often involving partial or complete

replacement of local populations (Smith & Ahern, 2013).

However, this migration from Lavant has not been uniform to

other hunter-gatherer populations across the globe. The

dispersal of agriculture from the Lavant region exhibits a

parallel pattern. Figure 3 shows the spread of farming from

Lavant dating back to 9,000 BCE, while farming in other world

regions appeared later in history.

Figure 3: Spread of farming

Migrations after the Great Flood

A significant event of the Great Flood

occurred, which, according to the Bible

and Quran,

came as a punishment to Prophet Noah’s nation. Following the

Great Flood, the descendants of Prophet Noah's sons—Ham, Shem,

and Japheth—initially settled in Africa, the Middle East and

Central Asia, respectively.

Subsequently, their progenies migrated to neighbouring

regions. Figure 4 shows these migratory patterns in terms of

geospatial and temporal dispersions. For example, we see a

pattern of Iranian farmers’ migration to Northwestern parts of

India, possibly from Shem’s children, much earlier than the

later migration of Central Asian pastorals to India, possibly

from Japheth’s children.

Figure 4: The prehistory of South Asia and

Europe are parallel in both being impacted by two successive

spreads, the first from the Near East after 7000 BCE bringing

agriculturalists who mixed with local hunter-gatherers, and

the second from the Steppe after 3000 BCE bringing people who

spoke Indo-European languages and who mixed with those, they

encountered during their migratory movement

Age of Abrahamic Prophets

Around 2000 BCE, the age of Abrahamic

prophets commenced. During this period, God’s judgement on a

select group of people, which became proof of God’s Judgment

for other nations, was primarily restricted to Abraham’s

progeny, notably with the rise and fall of the Israelites. The

Israelites experienced cycles of prosperity and decline,

reflecting their relationship with God. After Prophet Jesus,

the Israelites lost sovereignty, and the Ishmaelites rose to

prominence with Prophet Muhammad about 1400 years ago.

Ishmaelites experienced rise and fall cycles similar to

Israelites (Saleem, 2008).

Conclusion

Human history can be understood through a

multidisciplinary approach combining fossil evidence, genetic

analysis, isotopic data, archaeological findings, and

religious texts. This synthesis provides a comprehensive view

of human origins and development.

References

Gilligan, I. (2010). The prehistoric

development of clothing: Archaeological implications of a

thermal model. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory,

17(1), 15–80.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-009-9076-x

Higham, T., et al. (2014). Timing and

spacetime patterning of Neanderthal extinction. Nature,

512(7514), 306–309.

Meece, S. K. (2006). A bird’s eye view of

Çatalhöyük. Anatolian Studies, 56, 1–21.

Pearson, M. P. (1999). The archaeology of

death and burial. Sutton Publishing.

Prüfer, K., et al. (2014). The complete

genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains.

Nature, 505(7481), 43-49.

Richards, M. P., & Trinkaus, E. (2019).

Stable isotopes reveal patterns of diet and mobility in the

last Neandertals and first modern humans in Europe. Scientific

Reports, 9(1), March 2019.

Saleem, M. S. (2008). Shahadah: Witnessing

of the Truth. Renaissance – A Monthly Islamic Journal.

http://www.monthly-renaissance.com/issue/content.aspx?id=713

Smith, F. H., & Ahern, J. C. M. (Eds.).

(2013). The Origins of Modern Humans: Biology Reconsidered.

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Toups, M. A., Kitchen, A., Light, J. E., &

Reed, D. L. (2011). Origin of clothing lice indicates early

clothing use by anatomically modern humans in Africa.

Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28(1), 29–32.

https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msq234

Walker, P. L. (2001). A bioarchaeological

perspective on the history of violence. Annual Review of

Anthropology, 30(1), 573–596.

____________

|