(This writing is based on the views and insights of Javed

Ahmad Ghamidi expressed in his books and lectures)

Background

The Qur’an is a unique Book. It is God’s final guidance to

mankind. Before it, He revealed this guidance to many of His

messengers. After the Old and New Testaments, it is the Final

Testament of God. It presents the same religion that was

revealed to all the previous messengers of God. However,

contrary to the previous divine scriptures, it has been

preserved in its original language.

Its genre is different from books that we are generally used

to. It is thus essential for every serious student of the

Qur’an to have a basic understanding of its genre. If this

understanding can be supplemented to include its theme and

structure, the student may find this divine book much more

engaging. He will be enthralled by reading it and enchanted by

its nuances. It will captivate the mind and mesmerize the

heart. It will grip both intellect and emotion and transport

us to a domain of comprehension in which we are able to relish

the works and dealings of our Creator. We may not see God but

we may be able to experience Him by appreciating the ways He

speaks to human beings.

Genre

The Qur’an is a literary masterpiece which stands unparalleled

in the realm of human literature. If conventional

classifications are used, it is indeed difficult to categorize

the genre of this book. However, its closest similarity is to

a book of dialogues between real characters of 7th century

Arabia. These characters appear in a specific milieu and

converse with one another. Scenes and Acts change to bring one

or more of these characters on stage. These changes signify a

shift in the discourse. The Almighty Himself is the author of

these divine dialogues.

The word qala (to say) and its declensions which frequently

appear in the Book are a testimony to this dialogue-nature of

the Qur’an. Similar is the case with the frequent mention of

the invocative ya ayyu (O you …). At other instances, the

speaker and the spoken to, have to be ascertained through the

occasion and the context. In conventional dialogue works, the

name of the speaker is written by the author. In the case of

the Qur’an, this has to be understood by the reader.

Dialogues of the Plato, Dante’s “Divine Comedy” and Sir

Muhammad Iqbal’s “Javed Namah” are some works in the human

sphere that can be cited as parallels yet very rudimentary

examples of the genre of the Qur’an.

As far as the characters of the Qur’an are concerned, they can

be specified as:

Gabriel

Prophet(s)

Satan

Believers

Hypocrites

Polytheists

People of the Book (Jews and Christians)

A structured conversation between these characters of 7th

century Arabia can be observed in the words of God in the

Book. It originates from one of them and is directed to one or

more of them. These characters speak to each other and the

conversation rapidly shifts back and forth between these

characters. If these “leaps” of conversation are accounted

for, much of the apparent disjointedness of the discourse can

become meaningful as a well-directed dialogue between the

characters.

At times, the discourse is directed towards multiple

addressees. Sometimes, the words spoken take the form of a

powerful oration directed to specific addressees. At other

times, it is in the form of a monologue which is not

specifically directed towards anyone. Similarly, at times, the

nature of address is indirect. At still other times, an entity

is addressed but the direction of address is towards someone

else. Other instances show how what is said is actually said

in the heart but not uttered. Those who have a literary taste

can well appreciate these nuances and subtleties.

The nature and shift in address is a powerful tool that brings

out the tone of the speaker. It expresses emotions like love,

hate, rebuke and praise. At times the oration abruptly stops

to express anger. At other times, what is understood to be

implied is left out. Accounts of the previous prophets

typically suppress many details that are obvious. Sometimes,

the addressee cannot be determined from the beginning of a

dialogue: it gradually unfolds as the discourse proceeds

forth.

Such is the powerful nature of these utterances that they stir

the mind and stimulate the soul. The reader is captivated by

the profundity of arguments and is forced to form an opinion

because what is said does not merely constitute a compelling

intellectual argument couched in classical Arabic language; it

has repercussions on the life of a person. He is motivated to

adopt a certain attitude and to forsake another. He finds out

that what is at stake is of immense proportion. Arguments are

expressed to make a point. Many a time these arguments are

explicit and at other times they are expressed in a subtle way

in the form of oaths and adjurations. Linguistic tools that

are employed for this purpose need great attention. The most

common of these is the definite article alif lam. Many a time,

it specifies a particular entity it qualifies.

In short, the dialogue-nature of the Qur’an must be

appreciated to have a deeper understanding of this Book. It

has a point to prove and a purpose to achieve.

The obvious consequences of this dialogue nature of the Qur’an

are as follows:

1. It is essential to determine the primary addresser and

addressee of each surah. In other words, who among these

characters is speaking to whom. Within a surah they may shift

to a secondary addressee. The addresser may change as well.

2. The changes and shifts between the speaker and the spoken

to must be minutely and meticulously observed. Sometimes these

shifts are very subtle and at others very apparent. These

shifts also account for many apparent jumps, leaps and

disjointedness the reader may experience.

3. Characters or entities that were not present in 7th century

Arabia are not discussed simply because the dialogue is

between existing entities except if they are referred due to

some reason. Hence, Buddhism and Hinduism, for example, are

never brought up in the Qur’an for this very reason.

4. Since the foremost addressees of the Qur’an are the

entities living in Arabia, it will contain many localized

issues that relate only to the setting and culture of 7th

century Arabia. In this regard, it may be of interest to note

that certain beliefs of Arab Jews are discussed that were

specific to them, for example regarding Ezra (sws) to be the

son of God. It is known that other Jews do not have this

belief.

________

Together with this dialogue-genre of the Qur’an, its theme and

structure should also be understood. They are briefly

described below:

Theme

In order to understand the theme of the Qur’an, some

background needs to be understood.

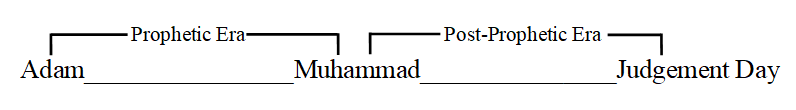

The religious history of mankind can be divided into two

distinct eras. The first era which occupies the major portion

of this history can be called the prophetic era. In this era,

the Almighty sent His representatives on earth to guide

mankind. They were called prophets (anbiya’). It began with

Adam (sws) and ended on Muhammad (sws). The second era, which

began with the demise of Muhammad (sws), will end on the Day

of Judgement is devoid of these representatives.

The first era has a feature which is wholly and solely

specific to it. It is in fact a certain unalterable practice

of God called sunnatullah by the Qur’an. The second era does

not have this feature. The Qur’an which was revealed in the

first era has eternally preserved this practice of God: this

practice is nothing but a divine scheme devised and executed

by God either through natural disasters or through His

messengers

and their followers and as such does not relate to the

shari‘ah (divine law) revealed by Him. Simply put, it is: God,

through natural disasters or through His messengers, punishes

and humiliates in this very world their foremost and direct

addressees who deliberately deny the truth communicated to

them by their respective messenger,

and rewards in this very world those among them who adhere to

the truth. In the case when this humiliation takes place

through the messengers and their followers, they act as

nothing but divine weapons. It is God’s retribution carried

out by God Himself. The purpose of this worldly retribution is

to make mankind mindful of the most important reality that it

tends to forget: reward and punishment in the Hereafter on the

basis of a person’s deeds. This reward and punishment, which

is to take place in the Hereafter, is substantiated visually

by the Almighty through the agency of His messengers so that

mankind may always remain heedful of this reality. The court

of justice which will be set up for every person on the Day of

Judgement was set up for the nations of messengers in this

world so that the latter could become a visual testimony to

the former. To put it another way: before the advent of the

greater Day of Judgement, several lesser days of Judgement

were brought about in this world in which people were rewarded

and punished on the basis of their deeds so that they could

become a visual evidence to the judgement that will take place

in the Hereafter. The Qur’an refers to this in the following

words: لِئَلاَّ يَكُونَ لِلنَّاسِ عَلَى

اللّهِ حُجَّةٌ بَعْدَ الرُّسُلِ (165:4) (so that

mankind after the coming of these messengers is left with no

excuse against the Almighty, (4:165)).

Owing to this specific feature of the prophetic era, certain

directives of the Qur’an are specific to this era and cannot

be extended to the post-prophetic era. This of course does not

mean that they lose their relevance to the post-prophetic era.

It only means that while they cannot be applied in this

post-prophetic era, their application in the prophetic era has

already afforded mankind with certain testimonies which have a

profound bearing on its attitudes towards life in this

post-prophetic era. It is imperative that the basis of the

directives of the Qur’an be understood in order to appreciate

which of them is confined to the prophetic era and which is

applicable to both eras. It is by not differentiating between

these directives that many misconceptions have arisen in

understanding the Qur’an.

It is in this background that the theme of the Qur’an can now

be put forth. It emerges from its subject-matter reflected in

its genre described earlier. This theme is a description of

the warning (indhar) delivered by Muhammad (sws) to his

foremost addressees that culminated in their worldly

punishment.

In other words, it was the last time that the established

practice of God referred to earlier came into play. The Qur’an

refers to this established practice in the following words:

وَلِكُلِّ

أُمَّةٍ رَّسُولٌ فَإِذَا جَاء رَسُولُهُمْ قُضِيَ بَيْنَهُم

بِالْقِسْطِ وَهُمْ لاَ يُظْلَمُونَ

For each community, there is a messenger. Then when their

messenger comes, their fate is decided with fairness and no

injustice is shown to them. (10:47)

It is an unrelenting law of God that relates solely to His

messengers:

سُنَّةَ

مَن قَدْ أَرْسَلْنَا قَبْلَكَ مِن رُّسُلِنَا وَلاَ تَجِدُ

لِسُنَّتِنَا تَحْوِيلاً.

Bear in mind the practice about the messengers We had sent

before you and you will not find any change in Our practice.

(17:77)

The above mentioned theme of the Qur’an is derived from it

subject matter as follows.

According to the Qur’an, while a prophet (nabi) merely

delivers glad tidings and warnings to his people, a messenger

(rasul), which is a special cadre among the prophets,

delivers glad tidings and warnings to his people in such a

conclusive way that they are not left with any excuse to deny

it. In the terminology of the Qur’an, this is called itmam al-hujjah:

رُّسُلاً

مُّبَشِّرِينَ وَمُنذِرِينَ لِئَلاَّ يَكُونَ لِلنَّاسِ عَلَى

اللّهِ حُجَّةٌ بَعْدَ الرُّسُلِ وَكَانَ اللّهُ عَزِيزًا

حَكِيمًا .

These messengers who were sent as bearers of glad tidings and

of warnings so that after them people are left with no excuse

which they can present before God. (4:165)

The Qur’an refers to the deliberate denial of the disbelievers

in the following words:

فَلَمَّا

جَاءهُم مَّا عَرَفُواْ كَفَرُواْ بِهِ فَلَعْنَةُ اللَّه عَلَى

الْكَافِرِينَ

So when there came to them that which they recognized, they

disbelieved in it. So let the curse of Allah be on the

disbelievers. (2:89)

It is after this phase of itmam al-hujjah that the divine

court of justice is set up on this earth. Punishment is meted

out to the rejecters of the truth and those who have accepted

it are rewarded, and, in this way, a miniature Day of

Judgement is witnessed on the face of the earth. It is evident

from the Qur’an that the various phases of the preaching

endeavour of a rasul include indhar (warning), indhar-i ‘am,

itmam al-hujjah

and hijrah wa bara’ah.

Each surah of the Qur’an is revealed in either of these phases

to which its content and context clearly testify.

By the itmam al-hujjah phase, the believers have become

distinct and segregated from the disbelievers and organized as

a separate unit. It is after this phase that the messenger

decides the fate of his nation on behalf of God. It is in

reality the Almighty who determines this task as pointed out

before.

It is evident from the Qur’an that in the Judgement phase, the

punishment of the disbelievers normally takes two forms

depending upon the situation that arises.

If a messenger has very few companions

and he has no place to migrate from his people and attain

political power, then he and his companions are sifted out

from their nation by the Almighty. Their nation is then

destroyed through various natural calamities like earthquakes,

typhoons and cyclones. The Qur’an says:

فَكُلًّا

أَخَذْنَا بِذَنبِهِ فَمِنْهُم مَّنْ أَرْسَلْنَا عَلَيْهِ

حَاصِبًا وَمِنْهُم مَّنْ أَخَذَتْهُ الصَّيْحَةُ وَمِنْهُم

مَّنْ خَسَفْنَا بِهِ الْأَرْضَ وَمِنْهُم مَّنْ أَغْرَقْنَا.

So each one of them We seized for their crime: of them,

against some We sent a violent tornado with showers of stones;

some were caught by a mighty blast; some We sunk in the earth;

and some We drowned in the waters. (29:40)

The ‘Ad, nation of Hud (sws), the Thamud nation of Ṣalih (sws)

as well as the nations of Noah (sws), Lot (sws) and Shu‘ayb (sws)

were destroyed through such natural disasters when they denied

their respective messengers as is mentioned in the various

surahs of the Qur’an.

In the case of Moses (sws), the Israelites never denied him.

The Pharaoh and his followers however did. Therefore, they

were destroyed.

In the second case, a messenger is able to win a fair number

of companions and is also able to migrate to a place where he

is able to acquire the reins of political power through divine

help. In this case, the messenger and his companions subdue

their nation by force. The forces of the messenger are

destined to triumph and humiliate his enemies. The punishment,

which in the previous case descended from the heavens, in this

case emanates from the swords of the believers. It was this

situation which arose in the case of Muhammad (sws). His

opponents were punished by the swords of the Muslims.

Referring to this form of divine punishment, the Qur’an

asserts:

قَاتِلُوهُمْ يُعَذِّبْهُمُ اللّهُ بِأَيْدِيكُمْ وَيُخْزِهِمْ

وَيَنصُرْكُمْ عَلَيْهِمْ.

Fight them and God will punish them with your hands and

humiliate them and help you to victory over them. (9:14)

فَلَمْ

تَقْتُلُوهُمْ وَلَـكِنَّ اللّهَ قَتَلَهُمْ.

[Believers!] It is not you who slew them; it was [in fact] God

who slew them. (8:17)

In other words, as pointed out earlier, it is the Almighty

Himself who punishes the immediate and direct addressees of

messengers if they deny their respective messengers; the

messengers and their companions are no more than a means of

carrying out this Divine plan.

The punishment and humiliation of nations towards whom

messengers were sent generally took place in two ways: nations

who primarily subscribed to monotheism were spared if they

accepted the supremacy of their respective messenger, while

nations who persisted with polytheism were destroyed. The

latter fate is in accordance with the fact that polytheism is

something that the Almighty never forgives:

إِنَّ

اللّهَ لاَ يَغْفِرُ أَن يُشْرَكَ بِهِ وَيَغْفِرُ مَا دُونَ

ذَلِكَ لِمَن يَشَاء وَمَن يُشْرِكْ بِاللّهِ فَقَدِ افْتَرَى

إِثْمًا عَظِيمًا

God never forgives those guilty of polytheism though He may

forgive other sins to whom He pleases. Those who commit

polytheism devise a heinous sin. (4:48)

Consequently, the Israelites were not wiped out as a nation

because, being the People of the Book, they were basically

adherents to monotheism. Their humiliation took the form of

constant subjugation to the followers of Jesus (sws) till the

Day of Judgement as referred to by the following verse:

إِذْ قَالَ

اللّهُ يَا عِيسَى إِنِّي مُتَوَفِّيكَ وَرَافِعُكَ إِلَيَّ

وَمُطَهِّرُكَ مِنَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُواْ وَجَاعِلُ الَّذِينَ

اتَّبَعُوكَ فَوْقَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُواْ إِلَى يَوْمِ

الْقِيَامَةِ.

Remember when God said: “O Jesus! I will give death to you

and raise you to Myself and cleanse you from those who have

denied; I will make those who follow you superior to those who

reject faith till the Day of Resurrection.” (3:55)

If this theme of the Qur’an is understood, there is a very

important consequence of it that must be appreciated. It

relates to the established practice of the Almighty that only

He has the authority to punish people for the crimes of

polytheism (shirk), disbelief (kufr) and apostasy (irtidad).

He did so through His messengers in the prophetic era and will

do it again on the Day of Judgement. However, in the

post-prophetic era, neither an individual nor a state has the

right to punish people for these crimes.

Structure

The Qur’an itself has alluded to its structure and format in

the following words:

وَلَقَدْ

آتَيْنَاكَ سَبْعًا مِّنَ الْمَثَانِي وَالْقُرْآنَ الْعَظِيمَ.

[O Prophet!] We have bestowed upon you seven mathani

which is the great Qur’an. (15:87)

If the implications of the above cited verse are unfolded, it

means that the Qur’an revealed by the Almighty to Muhammad (sws)

has seven distinct chapters and within each chapter surahs

occur in pairs with regard to their respective themes. This

pairing of surahs is very meaningful. Each member of a surah

pair complements the other in some way or another. Thus even a

cursory look can detect a similarity between Surah al-Ḍuha

(93) and Alam Nashrah (94) and between Surah al-Falaq (113)

and Surah al-Nas (114). A deeper deliberation will unfold this

similarity between other surah pairs. Some surahs are an

exception to this scheme as Surah al-Fatihah, which is like an

introduction to the whole Qur’an. Some other surahs like Surah

al-Nur (24) and Surah Ahzab (33) occur as a supplement or as a

conclusion of a chapter.

Following is a brief description of the seven Qur’anic

chapters indicating the place of revelation of each surah.

Chapter I {Surah al-Fatihah (1) - Surah al-Ma’idah (5)}

Makkan: (1)

Madinan: (2)-(5)

Chapter II {Surah al-An‘am (6) - Surah al-Tawbah (9)}

Makkan: (6)-(7)

Madinan: (8)-(9)

Chapter 3 {Surah Yunus (10) - Surah al-Nur (24)}

Makkan: (10)-(23)

Madinan: (24)

Chapter IV {Surah al-Furqan (25) - Surah al-Ahzab (33)}

Makkan: (25)-(32)

Madinan: (33)

Chapter V {Surah Saba (34) - Surah al-Hujurat (49)}

Makkan: (34)-(46)

Madinan: (47)-(49)

Chapter VI {Surah Qaf (50) - Surah al-Tahrim (66)}

Makkan: (50)-(56)

Madinan: (57)-(66)

Chapter VII {Surah al-Mulk (67) - Surah al-Nas (114)}

Makkan: (67)-(112)

Madinan: (113)-(114)

Some other features of these Qur’anic chapters are as follows:

1. Each chapter of the Qur’an begins with one or more Makkan

surah and ends with one or more Madinan surah. Both the Makkan

and Madinan surahs are in harmony and consonance with one

another in each chapter and relate to one another in the same

manner as roots and stems are related to their branches.

2. Within each chapter the sequence of the surahs is

chronological.

3. Each chapter discusses some aspect of the overall theme of

the Qur’an by delineating some phase(s) of the warning

delivered by Muhammad (sws) to his addressees. As such, each

chapter discusses some part of the phases of this warning.

4. Each chapter has its own theme around which its surahs

revolve. Following are the themes of each chapter:

Chapter I: (Fatihah (1) – Ma’idah (5))

The theme of the first chapter is to communicate the truth to

the Jews and Christians [of prophetic times] in a conclusive

manner, to institute a new ummah in their place, its spiritual

purification and segregation from the disbelievers and a

description of its final covenant with the Almighty.

Chapter II: (An‘am (6) – Tawbah (9))

The theme of the second chapter is communication of the truth

to the polytheists of Arabia in a conclusive manner, spiritual

purification of the believers and their segregation from the

disbelievers and a description of the last miniature Day of

Judgement witnessed in this world before the advent of the

greater Day of Judgement.

Chapter III: (Yunus (10) – Nur (24))

The theme of this chapter is to warn the Quraysh, to give glad

tidings to the Prophet (sws) and his followers of the

domination of the truth in Arabia and to spiritually purify

them and separate them from the disbelievers. The aspect of

glad tidings of dominance of the truth is prominent in this

theme.

Chapter IV: (Furqan (25) – Ahzab (33))

The theme of the fourth chapter is validation of the

prophethood of Muhammad (sws) and with its reference meting

out warnings and glad tidings to the Quraysh, the spiritual

purification of the believers and their segregation from the

disbelievers. In this regard, the status of Muhammad (sws) and

the Qur’an are explained to his followers.

Chapter V: (Saba’ (34) – Hujurat (49))

The theme of this chapter is validation of the belief of

monotheism and with its reference meting out warnings to the

Quraysh, giving glad tidings of the dominance of truth to the

Prophet (sws) his followers and the spiritual purification of

the believers and their segregation from the disbelievers.

Chapter VI: (Qaf (50) – Tahrim (66))

The theme of the fifth chapter is validation of the Day of

Judgement and with its reference meting out warnings and glad

tidings to the Quraysh, the spiritual purification of the

believers and their segregation from the disbelievers. The

requirements of obeying and submitting to God and His Prophet

are mentioned under this purification and segregation and

keeping in view the situation of that time.

Chapter VII: (Mulk (67) – Nas (114))

The theme of the seventh chapter is to warn the leadership of

the Quraysh of the consequences of the Hereafter, to

communicate the truth to them in a conclusive manner, and, as

a result, to warn them of a punishment, and to give glad

tidings to Muhammad (sws) of the dominance of his religion in

the Arabian peninsula.

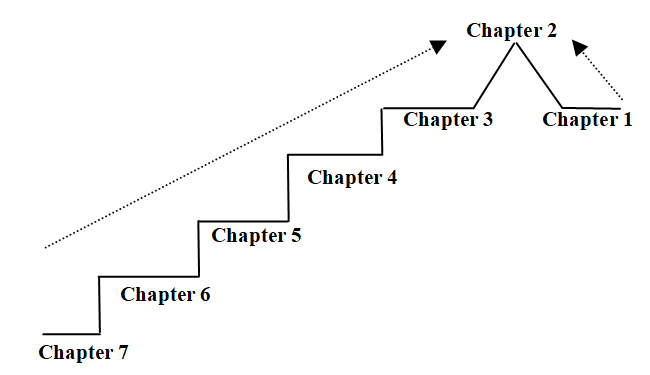

5. The sequence between the chapters can be understood from

the following illustration:

If we recall the theme of the Qur’an described earlier, it

was: a description of the warning (indhar) delivered by

Muhammad (sws) to his foremost addressees that culminated in

their worldly punishment. The two primary addressees were the

People of the Book of Arabia and the Polytheists of Arabia

belonging to the era of Muhammad (sws).

Chapter 2 depicts the worldly judgement of the direct and

foremost addressees of Muhammad (sws) and as such is the

culmination of the warning delivered by him. It can thus also

be regarded as the climax of the Qur’an. From chapter 7 to

chapter 3 the addressees are the Polytheists of Arabia and in

chapter 1 the addressees are the People of the Book. Chapter 2

portrays the fate of both these religious groups in this

world. In other words, the topic of indhar after passing

through various phases reaches its peak of worldly judgement

in this chapter from both sides. The only difference is the

addressees.

It may also be noted:

i. In chapters 6, 5, 4 and 3, besides the theme of delivering

warnings, the theme of spiritual purification of the believers

and their segregation from the disbelievers is also added.

ii. Chapter 1 has been placed the foremost because the

recipients of the Qur’an are its addressees the foremost.

iii. Except for chapter 1, the Makkan surahs of each chapter

discuss delivering of warnings and glad tidings and of

communicating the truth to the addressees in a conclusive

manner, while the Madinan surahs discuss the spiritual

purification and segregation of the believers.

It can thus be concluded that the description of the miniature

day of judgement that happened in Arabia as a consequence of

Muhammad’s conclusive communication of the truth has been

eternally preserved in the Qur’an in this beautiful sequence.

In other words, the Qur’an validates to the ultimate extent

this premise of religion that one day a greater day of

judgement will be set up for all the people of this world.

Conclusion

In the foregoing paragraphs, the genre of the Qur’an, its

theme and structure are described to introduce this divine

Book to the common reader. It is in the form of divine

dialogues that are preserved in a meaningful format with a

specific theme.

It has been revealed by the Lord of the heavens and the earth

purely for the guidance of earthlings. Let them read it for

this purpose!

Introducing Al-Bayan

As a student of Javed Ahmad Ghamidi (www.javedahmadghamidi.com),

I would like to introduce his annotated translation of the

Qur’an published in five volumes in Urdu.

It is called Al-Bayan. Most readers may already be familiar

with it. This annotated translation brings out the dialogue

genre of the Qur’an described earlier. The theme and structure

of the Qur’an referred to earlier are also encapsulated in

this translation.

Readers are may find it useful for their study.

_________________________

|