|

I. Introduction

Muslim sources are quite unanimous in stating the fact that

the text of the earliest masāhif was in bare consonantal form

– devoid of diacritics (i‘jām) to distinguish homographs and

bereft of vowels markings (tashkīl or i‘rāb) to discern

declensions. The script which needed a total of twenty eight

constants from the available fifteen graphemes, and which was thus without

matres lectionis

posed difficulty for non-Arabs. In order to avoid misreading

of these masāhif, vocalization and diacritics

were gradually introduced in the script. This process began

about three decades after the demise of Muhammad (sws) and was

completed in about the next one hundred years.

In this article, an attempt will first be made in the light of

primary source books to trace these major phases of the

development of Qur’ānic orthography specifically related to

vocalization and diacritics. Later this account will be

critically evaluated. The discussion will end on a conclusion.

II. The Traditional Accounts

In the light of the early sources, the phases of development

of Qur’ānic orthography specifically related to vocalization

and diacritics can be chronologically divided into the

following three:

A. The First Vocalization Phase

B. The Diacritics Phase

C. The Second Vocalization Phase

Details follow.

A. The First Vocalization Phase

Almost all Muslim authorities are of the opinion that the

first person to introduce vocalization on the masāhif was a

Basran poet and literary figure called Abū al-Aswad Zālim ibn

‘Umar al-Dū’alī (d. 69 AH). He embraced faith when the Prophet

(sws) was alive but was never able to see him.

He was a close companion of ‘Alī (rta) from whom he has

reported to have learnt the basic rules of Arabic grammar and

then formally documented them.

Majority of the sources mention that it was at the behest of

Ziyād ibn Abīh (d. 53 AH), the Basran governor of the Umayyad

caliph Mu‘āwiyah ibn Abū Sufyān (d. 60 AH) that Abū al-Aswad

undertook this task,

while a very minority opinion is that he did it at the behest

of the Umayyad caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān (d. 86 AH).

Muhammad ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Amr al-‘Utbī (d. 228 AH) has

recorded in detail this event of first vocalization:

حدثني أَبي قال : حدثنا أَبو عكرمة قال :

قال الْعُتْبي : كتب مُعاوية إلى زياد يَطلبُ عبيد الله ابنه ،

فلما قدِم عليه كلّمه فوجَده يلحَن فرده إلي زياد ، وكتب إليه

كتاباً بلومه فيه ، ويقول : "أمثلُ عُبَيْد الله يُضَيع".فبَعث

زياد إِلى أَبي الأسود فقال له : يا أَبا الأَسود ، إِن هذا

الحمراء قد كثُرتْ وأفسدَت من أَلسُن الْعرب فلو وضعتَ شيئاً

يَصلِح به الناس كلا مهم ويُعربون به كتاب الله. فأَبى ذلك أَبو

الأَسود وكره إجابة زياد إلي ماسأَل. فوجه زياد رجلاً وقال له :

اقعُد في طريق أَبي الأَسود فإِذا ربك فاقرأ شيئاً من القرآن

وتعمد اللحن فيه ففعل ذلك ، فلما ربه أبو الأسود رفع الرجل صوته

يقرا : (أَن اللهَ بَرِي مِّن المشركين و رَسوله) فاستعظم 10

/ أ ذلك أَبو الأَسود وقال : عزَّ وجه

الله أَن يَبرا من رسولِه ، ثم رجع من فوره إلى زياد فقال له :

يا هذا قد أَجبْتُك إلي ما سأَلتَ ، ورأَيت أَن أَبدأَ باعراب

الْقرآن فابعَثْ إِليّ بثلاثين رجلاً. فأَحضَرَهم زياد فاختار

منهم أَبو الأَسود عشرة ثم لم يزل يختارُهم حتى اختار منهم رجلا

من عبد القَيْس فقال : خُذ الْمُصحف وصِبْغاً يخالفُ لون المِداد

، فإِذا فتحتُ شفتيّ فانقُط واحدة فوق الحرف ، وإذا ضممتُها

فاجعل النُّقطة إِلى جانب الحرف ، وإذا كسرتُها فاجعل النُقطة في

أَسفله ، فإِن أَتبعْتُ شيئاً من هذه الحركات غنَّة فانقط نقطتين

. فابتدأَ بالمصحف حتى أَتي على آخره ثم وضع المختصر المنسوب

إليه بعد ذلك.

‘Utbī stated: “[Once] Mu‘āwiyah (rta) wrote a letter to his [Basran

governor] Ziyād [ibn Abīh] to call over his son ‘Ubaydullāh

ibn Ziyād to him. When the latter came over to him, he spoke

to him and detected many mistakes in his language; Mu‘āwiyah (rta)

sent him back to his father. He then wrote a letter to Ziyād

censuring him in it and said: ‘[Those] like ‘Ubaydullāh should

be done away with.’ Ziyād then wrote to Abū al-Aswad and said

to him: ‘These non-Arabs have increased a lot and have spoiled

the language of the Arabs; I wish you could do something

through which people correct their language and correctly read

the Book of God.’ However, Abū al-Aswad refused to do so and

showed his dislike in responding to Ziyād’s request. So Ziyād

went to a person and asked him: ‘Sit beside Abū al-Aswad’s way

and read something from the Qur’ān and intentionally make a

mistake in reading it.’ When Abū al-Aswad passed by that way,

the person loudly read the following Qur’ānic verse:

أَنَّ اللّهَ بَرِيءٌ مِّنَ الْمُشْرِكِينَ

وَرَسُولِهِ.

When Abū al-Aswad heard this, he got very alarmed and said:

‘God’s countenance is more powerful than to show acquittal to

His Messenger.’ He then immediately came to Ziyād and said: ‘I

will do what you asked for and I will vocalize the Qur’ān (put

i‘rāb on it); so send over thirty people.’ Ziyād duly provided

him with these. From these thirty, Abū al-Aswad selected ten

and continued [to test them] until from these ten, he selected

a single individual from the tribe of ‘Abd al-Qays.

He asked this person: ‘Take a mushaf and some ink which should

be of a different colour than the colour of the script. When I

open my lips, write a dot on top of the letter; when I close

both lips, write a dot adjacent to that letter; when I lower

my lips write a dot below that letter; If I follow up these

signs with [the sound of] nunation (ghunnah), write two dots

[accordingly].’ So Abū al-Aswad began with this task with a

mushaf until he came to the end. Then he wrote a concise book

ascribed to him [on this subject].”

Mūsā Shāhīn Lāshīn attributes this whole incident to around 48

AH while referring to an unspecified source.

Some other secondary sources mention that whenever this scribe

would complete one page, Abū al-Aswad would check it.

Jurjī Zaydān has mentioned seeing a Kufic mushaf dotted

according to this scheme of Abū al-Aswad written on thin

parchment at the Dār al-kutub al-misriyyah which was actually

found at a mosque in Cairo.

It is also surmised by some scholars from the description of

the endeavour undertaken by Abū al-Aswad that he only

vocalized the last letter of words.

In the opinion of Lāshīn,

it was ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān who asked his Iraqī governor

al-Hajjāj ibn Yūsuf (d. 95 AH) to stop tashīf which was still

creeping in and people were making mistakes in reading. Lāshīn

says that around 80 AH al-Hajjāj summoned Nasr ibn ‘Asim al-Laythī

(d. 89 AH) who then vocalized every letter of a word so as to

minimize reading errors.

Hifnī Nāsif (d. 1337 AH) is of the opinion that the nuqat

(dots) of Abū al-Aswad were generally adopted in the masāhif;

as far as other books were concerned, they were rarely

adopted.

He goes on to point out some of the innovations made by the

followers of Abū al-Aswad in adopting his methodology of nuqat.

Some of them adopted a square shape for representing the nuqat

and others adopted a hollow circular shape and some others a

non-hollow circular shape. More orthographic signs were added

by his followers to represent sukūn and alif al-wasl.

In this regard, we also find scholars engaged in a discussion

about the origination of these nuqat. Some of them are of the

opinion that Abū al-Aswad was not the originator of the nuqat.

He only applied this methodology which he learnt from the

Syrians who used them in their own language: Syriac.

Some scholars are of the view that he was the originator of

this methodology.

Some other scholars are of the view that he only revived this

methodology which he learnt from the Arabs and which was in

vogue in Arabia earlier.

B. The Diacritics Phase

Perhaps the earliest source which mentions anything about the

insertion of diacritics to distinguish similar characters in

the mushaf is Kitāb al-tanbīh ‘alā hudūth al-tashīf of Hamzah

ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī (d. 360 AH).

It records the reason for insertion of diacritics: more than

forty years passed after the five ‘Uthmānic Qur’āns were

written and sent to various parts of the empire till the era

of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān arrived. During this time, a lot

of tashīf (misreading of script) came into being because the

script of many letters (eg. الباء ، التاء ،

الثاء) resembled each other and they were not

distinguishable from one another. This worried al-Hajjāj and

he asked his scribes to make signs which could distinguish

similar letters from one another. These scribes inserted one,

two or three diacritics above or below the similar letters to

make them distinct from one another. Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī (d.

382 AH) while referring to the same details as referred to by

Hamzah ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī adds that as per one opinion,

al-Hajjāj summoned Nasr ibn ‘Āsim al-Laythī (d. 89 AH) for

this purpose. He writes:

وقد رُوی أنّ السبب

فی نَقْط المصاحف أن الناس غَبَرُوا يقرءون فی مصاحف عثمانَ رحمةُ

الله عليه ، نيِّفا وأربعين سنة ، إلى أيام عبد الملك بن مروان.

ثم كثر التصحيف و انتشر بالعراق ، ففزِع الحجَّاجُ إلى كُتاَّبه

، وسألهم أن يضعوا لهذه لحروف المشْتَبِهةِ علامات. فيقال: إنّ

نصَر بن عاصم قام بذلك ، فوضع لنَّقط أفرادا وأزواجا. وخالف بين

أما كنها بتوقيع بعضها فوق الحروف ، وبعضها نحت الحروف

It has been reporteed that the reason for putting dots on the masāhif was that more than forty years had passed since the

people were reading the masāhif of ‘Uthmān (rta) till the time

of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān arrived. Misreading [of the

masāhif] increased and spread to Irāq. At this al-Hajjāj,

worriedly turned to his scribes and asked them to put signs on

similar letters. It is said that Nasr ibn ‘Āsim undertook this

task. He instituted one and two dots and placed them variously

by putting some at the top of the letters and some at the

bottom.

Al-Dānī has described the details of these distinguishing

marks recorded on letters which resembled one another.

Scholars are of the opinion that Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar (d. 89 AH)

and Muhammad ibn Sīrīn (d. 110 AH) were also summoned by al-Hajjāj

for this objective.

They base their view on the following data:

وأما شكل المصحف

ونقطه فروي أن عبد الملك بن مروان أمر به وعمله فتجرد لذلك

الحجاج بواسط وجد فيه وزاد تحزيبه وأمر وهو والي العراق الحسن

ويحيى بن يعمر بذلك

As far as the shakl and nuqat of the masāhif are concerned, it

is reported that ‘Abd al-Malik ordered for it and had it done.

He specifically deputed al-Hajjāj for this task in [the city

of] Wāsit. Al-Hajjāj expended his effort in this task and also

added divisions to the mushaf. It was while he was the

governor of Iraq that he ordered al-Hasan al-Basrī and Yahyā

ibn Ya‘mar to do this.

C. The Second

Vocalization Phase

It is surmised by Muslim scholars of Qur’ānic orthography that

the nuqat of masāhif (both tashkīl and i‘jām) continued in the

way they were formulated till the time of al-Khalīl ibn Ahmad

al-Farāhīdī (d. 170 AH). He was a grammarian and a philologist

known to have authored the first dictionary of the Arabic

language (Kitāb al-‘ayn). He was also the originator of the

discipline of prosody.

He introduced a major change in the nuqat of tashkīl. The

reasons for this change as pointed out by Sharshāl

was that before his times, writing down of the masāhif needed

inks of two colours – one for tashkīl and the other for i‘jām.

Also this would fill up a page with dots distinguishable with

colours only. This caused difficulty both for the readers and

the scribes. The situation could only be resolved by changing

one of the two types of nuqat; the nuqat of i‘jām had become

part of the letters and were also of the same ink as the

letters and hence it was not appropriate to change them. So

al-Khalīl is said to have changed the nuqat of tashkīl into

shapes from which evolved the signs of dammah, kasrah and

fathah we know today. Al-Dānī records:

وقال أبو الحسن

بن كيسان قال محمد بن يزيد الشكل الذي في الكتب من عمل الخليل

وهو مأخوذ من صور الحروف فالضمة واو صغيرة الصورة في أعلى الحرف

لئلا تلتبس بالواو المكتوبة والكسرة ياء تحت الحرف والفتحة ألف

مبطوحة فوق الحرف

Muhammad ibn Yazīd al-Mubarrad records: the shakl found in

books is the work of al-Khalīl and is adapted from the

depiction of the letters. So the dammah is represented in the

form of a small waw above a letter so that it does not get

mixed up with [the actual] waw written; and the kasrah is in

the form of a yā written below a letter and the fathah is

written in the form of alif placed horizontally above a

letter.

Al-Dānī further adds that al-Khalīl also originated al-hamz,

al-tashdīd, al-rawm and al-ishmām.

Scholars like Ghānim Qadūrī and Sharshāl

are of the view that Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī has referred to this

endeavour of al-Khalīl as well. After describing the nuqat of

al-‘ijām carried out by Nasr ibn ‘Āsim at the behest of al-Hajjāj,

al-‘Askarī writes:

فَغَبَر الناس بذلك زمانا لا يكتبون إلا

منقوطا. فكان مع استعمال النقط أيضا يقع التصحيف ، فأحدثوا

الإعْجام ، فكانوا يُتْبِعون النَّقط بالإعجام. فإذا أُغْفِل

الاستقصاءُ على الكلمة فلم تُوَفَّ حقوقَها اعترى هذا التصحيفُ ،

فالتمسوا حيلةً ، فلم يقْدِروا فيها إلا على الأخذ من أفواهِ

الرجال.

People stuck [to this method of Nasr] for many years and would

not write [masāhif] without nuqat. But even after using nuqat,

misreading [of the masāhif] continued. So they invented i‘jām

and used i‘jām with nuqat as well. A slight carelessness in

putting in all i‘jām with nuqat on words again resulted in

misreading [of the masāhif]. People looked for a further

method [to secure the correct reading] but were not able to

find one except for acquiring [the Qur’ān] from the mouths of

people.

In their opinion, the word i‘jām refers to shakl because

linguistically shakl means i‘jām

and hence the reference to i‘jām here alludes to the endeavour

of al-Khalīl.

In this regard, scholars have grappled with a question since

sources cite conflicting reports about the person who

originated the nuqat on the mushaf. Thus there are some

sources which say that the first one to put nuqat on the

mushaf was Abū al-Aswad (69 AH); some say that it was Nasr ibn

‘Āsim al-Laythī (89 AH) and some say that it was Yahyā ibn

Ya‘mar al-‘Udwānī (89 AH).

Those which record this fact about Abū al-Aswad include al-Zubaydī

(d. 379 AH),

Abū Hilāl al-‘Askarī (395 AH),

Ibn al-Jawzī (597 AH),

Yāqūt al-Hamawī (626 AH),

al-Safadī (764 AH),

al-Qurtubī (d. 791 AH),

al-Qalqashandī (821 AH),

Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH),

al-Suyūtī (d. 911 AH),

and Sayyid al-Mar‘ashī (1425 AH).

Those which record this fact about Nasr ibn ‘Āsim include al-Dānī

(d. 444 AH),

Ibn Atiyyah (d. 543 AH AH),

al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH),

Muhammad ibn Yaqub al-Fayrūzābādī (d. 816 AH),

Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 833 AH),

and al-Yaghmūrī (d. 845 AH),

and Tāshkubrāzādah (d. 962 AH).

Those which record this fact about Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar include

Ibn Abī Dā’ūd (d. 316 AH),

al-Dānī (d. 444 AH),

Ibn Atiyyah (d. 543 AH),

al-Mizzī (d. 743 AH),

Ibn Kathīr (d. 772 AH),

al-Dhahabī (d. 774 AH),

Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 833 AH),

Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH),

al-Yaghmūrī (d. 845 AH),

and Jamāl al-Dīn (d. 874 AH),

al-Suyūtī (d. 911 AH),

and Tāshkubrāzādah (d. 962 AH).

Another name which is also cited in this regard is that of

‘Abdullāh ibn Abī Ishāq al-Hadramī (d. 117 AH).

Most scholars while trying to resolve these conflicting

reports say that the nature of nuqat put by Abū al-Aswad and

the ones put by Nasr and Yahyā was different and all three of

them were pioneers in this regard; thus Abū al-Aswad was the

first to put the nuqat related to i‘rāb (vocalization) while

Nasr and Yahyā were the first to put the nuqat related to

i‘jām (diacritics).

III. Critical Evaluation of the Accounts

The following questions and objections arise on each of the

three phases in the aforementioned accounts of the early

development of Qur’ānic orthography related to vocalization

and diacritics.

A. The First Vocalization Phase

1. If Abū al-Aswad (d. 69 AH) was the first person to put

vowel marks on the masāhif in the form of nuqat, then the

question arises that why did not anyone of his students or

even the students of his students report this endeavour from

him. Following are the students of Abū al-Aswad recorded by

al-Mizzī:

Sa‘īd ibn ‘Abd al-Rahmān ibn Ruqaysh (d. ?), ‘Abdullāh ibn

Buraydah (d. 115 AH), ‘Umar ibn ‘Abdullāh, mawlā Ghufrah (d.

145 AH) Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar (d. 89 AH), Abū al-Harb ibn Abī al-Aswad

(d. 109 AH). To this list, the following more students can be

added on the authority of Abū Sa‘īd al-Sayrāfī:

‘Anbasah ibn Ma‘dān (100 AH), Maymūn al-Aqran (d. ?) and as

per an opinion Nasr ibn ‘Āsim (d. 89 AH).

On the contrary, some of these students do report another

feat: he was the originator of the science of nahw (Arabic

grammar).

Thus, one of Abū al-Aswad’s students, Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar (d. 89

AH), reports that Abū al-Aswad, at the behest of ‘Alī (rta),

was the originator of the science of nahw (Arabic syntax) when

he saw his daughter reading the expression

ما أشد الحر

in an erroneous manner.

Similarly, another of Abū al-Aswad’s students, Abū al-Harb ibn

Abī al-Aswad (d. 109 AH), says that when his father Abū al-Aswad

was asked the source from which he obtained the science of

nahw, he replied that he derived its definitions from ‘Alī (rta).

At another instance Abū al-Harb says that the first chapter

which his father formulated on nahw was the chapter on [words

of] amazement (ta‘ajjub).

In other words, had he been the originator of nuqat on the

masāhif, his students would have reported this feat of his as

well just as they have reported his feat of originating Arabic

grammar. It may also be noted that there are many authorities

who have recorded this feat of his (origination of nahw). They

have not even referred to the fact that he was responsible for

putting nuqat on the masāhif.

This casts doubt on the fact that he was actually responsible

for such an endeavour.

2. It is more than a hundred years after Abū al-Aswad’s

endeavour (reported to have taken place around 40 AH) that

anyone ascribes the introduction of vocalization to Abū al-Aswad.

The first person to do so is Abū ‘Ubaydah Ma‘mar ibn Muthannā

(d. 209 AH).

Following are the other three who report this achievement from

him and are even later:

i. Abū al-Hasan ‘Alī ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullāh al-Madā’inī

(d. 225 AH)

ii. Muhammad

ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Amr al-‘Utbī (d. 228 AH)

iii. Muhammad ibn Yazīd al-Mubarrad (d. 286

AH)

It is known that Abū al-Aswad died in 69 AH.

So, none of the above narrators is contemporaneous to him and

thus could not have heard directly from him or seen him.

3. Not only are the above referred to reports munqata‘,

they have other problems in their chains as well. Let us now

examine all the isnād of the incidents ascribed to Abū al-Aswad

in chronological order:

i. Abū ‘Ubaydah

Ma‘mar ibn Muthannā (d. 209 AH)

ii. Abū al-Hasan ‘Alī ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullāh al-Madā’inī

(d. 225 AH)

iii. Muhammad

ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Amr al-‘Utbī (d. 228 AH)

iv. Muhammad ibn Yazīd al-Mubarrad (d. 286

AH)

Here are the full chains of

narration for each.

i. Abū ‘Ubaydah

Ma‘mar ibn Muthannā (d. 209 AH)

This has no chain of narration and probably the foremost

person to cite it is Abū Sa‘īd al-Sayrafī (d. 368 AH) in his

Akhbār al-nahwiyyīn al-basriyyīn.

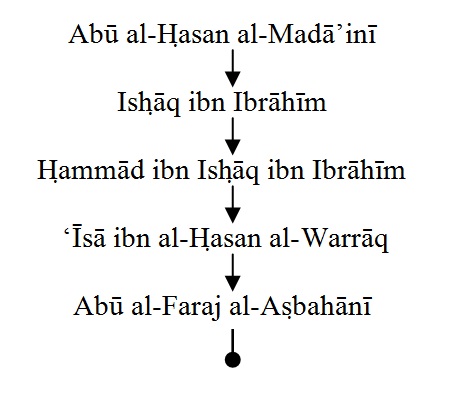

ii. Abū al-Hasan

‘Alī ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullāh al-Madā’inī (d. 225 AH)

Following is

the jarh on some of its narrators:

a. ‘Īsā ibn al-Hasan al-Warrāq

No tawthīq is available on him in rijāl books. Hence, he is

majhūl al-hāl.

b. Hammad ibn

Ishāq ibn Ibrāhīm al-Mūsilī

No tawthīq is available on him in rijāl books. Hence, he is

majhūl al-hāl.

c. Abū al-Hasan

‘Alī ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullāh al-Madā’inī

Ibn Adī says

that he is laysa bi al-qawī fī al-hadīth.

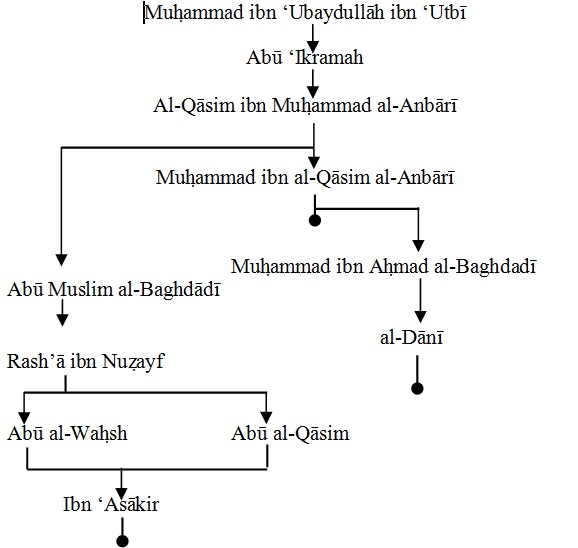

iii. Muhammad

ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Amr al-‘Utbī

(d. 228 AH)

Following is

the jarh on some of its narrators:

a. Abū ‘Ikramah

‘Amir ibn ‘Imrān ibn Ziyād al-Dabbī

No tawthīq is available on him in rijāl books. Hence, he is

majhūl al-hāl.

b. Muhammad ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Amr al-‘Utbī

Ibn Qutaybah, al-Safadī and Ibn Khallikān record the following

jarh on him: kāna mushtahiran bi al-sharāb.

On a similar note, al-Dhahabī records: kāna

yashribu.

iv. Muhammad ibn Yazīd al-Mubarrad (d. 286

AH)

This has no chain of narration. Al-Dānī cites him in his Al-Muhkam.

As far as the reports are concerned which say that the first

person to put nuqat on the masāhif was Abū al-Aswad, the first

person to narrate such a report is al-Zubaydi (d. 379 AH) in

his Tabaqāt with reference to al-Mubarrad (d. 286 AH). The

inqitā‘ here is obvious too!

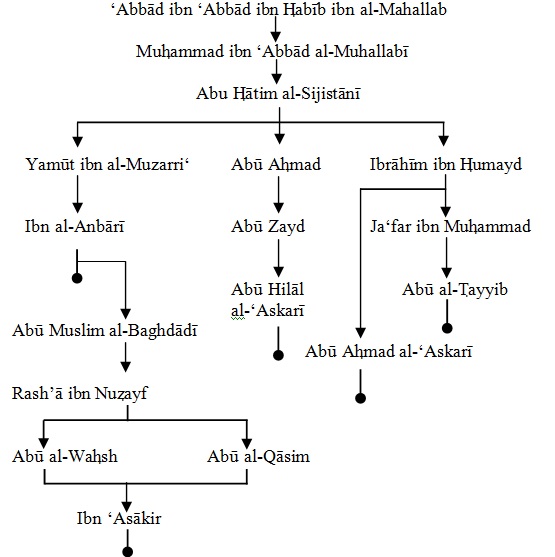

4. The accounts of Al-Mada’ini (d. 225 AH) and ‘Utbī (228 AH)

cited earlier mention that Abū al-Aswad was induced to put

nuqat on the masāhif when he heard someone wrongly reading a

verse of Sūrah Tawbah. On the other hand, it is reported by

‘Abbād ibn ‘Abbād ibn Habīb al-Mahallab

(d. 181 AH) that when Abū al-Aswad heard someone wrongly

reading the masāhif, he resolved to institute grammar (not

nuqat). Furthermore, there is yet another report by Ibn Abī

Malaykah (d. 117 AH) (see point 9 ahead) which says that it

was this very verse of Sūrah Tawbah which was wrongly taught

to and read by a Beduoin. When ‘Umar heard of this, he asked

Abū al-Aswad to institute the rules of grammar (again no

mention of nuqat).

So it is strange that the same verse of Sūrah Tawbah occurs:

i. at times to induce Abū al-Aswad to institute grammar and at

times to institute the nuqat.

ii. at times in an incident in the time of ‘Umar (rta) and at

times in the times of Mu‘āwiyah (rta) to induce its listener

to two different acts.

‘Abbād’s report may be illustrated thus:

a. ‘Abbād ibn ‘Abbād ibn Habīb ibn al-Mahallab

Al-Mizzī

records that in the opinion of Abū Hātim, he is lā yuhtajju bi

hadīthihī. Though at one place Ibn Sa‘d states: thiqah wa

rubbama ghalita,

at another place, his words about him are: lam yakun bi al-qawī

fī al-hadīth.

Ibn Hajar

says about him: thiqah rubbamā wahima.

b. Muhammad ibn ‘Abbād al-Muhallabī

Al-Khatīb al-Baghdādī records:

lam yakun basīran bi al-hadīth (he is not

intelligent in matters of hadīth) and according to al-Harbī is

guilty of misspelling words (tashīf); he altered

بقرة to

بهرة and

ابن جابر to

ابن جدير.

It is perhaps because of this that Abū Hātim’s opinion about

him is: lam aktub ‘anhū shay’

(I have not written anything from him).

It may thus be observed that the report of ‘Abbād (d. 181 AH)

has problems in its chain of narration. However, since the

reports of Ibn Abī Malaykah

(d. 117 AH), al-Madā’īnī (d. 225 AH) and al-‘Utbī (d. 228 AH)

themselves suffer from flaws in their chains of narration

hence it was deemed appropriate to compare the four with one

another.

5. An interesting point to note in Mubarrad’s account (as

opposed to the rest of the three) is that Abū al-Aswad set

about instituting the rules of grammar by putting nuqat on the

masāhif: apparently the two have no connection. This act

obviously could only safeguard correctly reading the masāhif

and not in helping people learn Arabic grammar.

6. The first book in which Abū al-Aswad’s nuqat accounts

are recorded is Al-Waqf wa al-Ibtidā’ by Ibn al-Anbārī (d. 328

AH). However, at least five major works prior to Al-Waqf wa

al-Ibtidā’ which record biographical entries on Abū al-Aswad

are devoid of any nuqat mention. The question arises: Why?

Here are the details:

i. Al-Tabaqāt by Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230 AH)

Ibn Sa‘d gives a short biographical entry on Abū al-Aswad in

which says that he was a poet and became the governor of

Basrah. Similarly, it also contains a note on Ziyād ibn Abīh;

but these entries are devoid of any mention of Abū al-Aswad

inserting nuqat.

ii. Tabaqāt fuhūl al-shu‘arā’ by Muhammad ibn Salām al-Jumahī

(d. 232 AH)

Al-Jumahī gives a short biographical entry on Abū al-Aswad

which says that he was the first to institute the rules of

Arabic but does not mention anything about his role in nuqat.

iii. Ma‘rifah al-Thiqāt by al-‘Ijlī (d. 261 AH)

He records that Abū al-Aswad is from among the prominent

tābi‘ūn, a companion of ‘Alī (rta) and a person who was the

first to talk about about nahw. However, he records nothing on

his contribution to nuqat.

iv. Al-Ma‘ārif by Ibn Qutaybah (276 AH)

Ibn Qutaybah gives a short biographical entry on Abū al-Aswad

which says that he was a poet, was the first to formulate the

rules of Arabic and became the governor of Basrah but does not

mention that he had any role in introducing nuqat on the

masāhif.

v. Al-jarh wa al-ta‘dīl by Ibn Abī Hātim (d. 327 AH)

Ibn Abī Hātim gives a short biographical entry on Abū al-Aswad

in which he records his real name (Zālim ibn ‘Amr), states

that he is a reliable narrator and is also the first who

formulated nahw. The entry is devoid of any mention of his

feat of inserting nuqat on the masāhif.

It is from the first quarter of the fourth century onwards

that we find books recording accounts which attribute

introduction of nuqat on the masāhif by Abū al-Aswad. These

works include: Marātib al-nahwiyyīn

by Abū al-Tayyib (d. 351 AH), Kitāb al-Aghānī

by Abū al-Faraj (d. 356 AH), Akhbār Al-nahwiyyīn

by al-Sayrāfī (d. 368 AH), Tabaqāt al-nahwiyyīn

by al-Zubaydī (d. 379 AH), Fihrist

by Ibn Nadīm (d. 385 AH), Al-Muhkam

by al-Dānī (d. 444 AH), Tārīkh Madīnah Dimashq

by Ibn ‘Asākir (d. 571 AH), Nuzhat al-alibbā’

by Ibn al-Anbārī (d. 577 AH), Inbā’ al-ruwāt

by al-Qiftī (d. 624 AH).

In this regard, perhaps the first historian to say that Abū

al-Aswad was the first person nuqat on the masāhif is Ibn

al-Jawzī

(d. 597 AH) and he does not mention various accounts which

record Abū al-Aswad’s endeavour. He merely records that Abū

al-Aswad was the first to put nuqat on the masāhif. Similar

statements are recorded by Yāqūt al-Hamawī

(626 AH), al-Safadī (764 AH)

and al-Dhahabī

(d. 748 AH).

However, there are works even after the first quarter of

the fourth century right up to the ninth century which mention

biographical information about Abū al-Aswad but do not state

that he had any role in recording nuqat on the masāhif. These

include:

i. Al-Thiqāt by Ibn Hibbān (d. 354 AH)

Ibn Hibbān does record that Abū al-Aswad took part in the

battle of Siffīn, was deputed as a governor of Basrah and was

the first to institute nahw.

ii. Al-Ta‘dīl wa al-tajrīh

by al-Bājī

(d. 464 AH)

Al-Bājī records various opinions about his name, that he

was the first to institute nahw, was a reliable a narrator and

died in the plague of 69 AH.

iii. Usud al-Ghābah by Ibn Athīr (d. 630 AH)

Ibn Athīr does record that Abū al-Aswad was not able to

acquire the companionship of the Prophet (sws), was a famous

tābi‘ī, was companion of ‘Alī (rta) who made him the governor

of Basah and was the first to institute nahw, was a poet and a

profound literary figure.

iv. Al-Bidāyah wa al-nihāyah by Ibn Kathīr (d. 772 AH)

Ibn Kathīr gives a short biographical entry on Abū al-Aswad

which among other details says that he was the first to

formulate the rules of Arabic.

v. Tārīkh of Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808 AH)

Ibn Khaldūn mentions the fact that Abū al-Aswad was the first

person to formulate Arabic grammar.

All this data cast serious doubts on this alleged role

ascribed to Abū al-Aswad.

7. In this regard, it may be noted that the strangest omission

of Abū al-Aswad’s endeavour is in the Kitāb al-masāhif

of Ibn Abī Dā’ūd (d. 316 AH).

The whole book has copious information about directives and

issues related to the masāhif. It has a section on nuqat

al-maāhif which is rich in information on the subject. It has a

narrative which says that the first person to put nuqat on the

masāhif was Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar;

it mentions narratives which record the names of early

authorities who disliked putting nuqat on the mushaf and

others who did not see any harm in it;

it mentions a narrative which records the opinion of al-Hasan

al-Basrī that charging money for putting nuqat on masāhif was

not a problem;

it records a detailed narrative on the authority of Abū Hatim

Sijistanī on the methodology of putting nuqat on masāhif.

The initial part of the narrative even describes the same

scheme as that of Abū al-Aswad but without taking his name. It

is quite strange that in the wake of all these details, there

is no mention of Abū al-Aswad and his endeavour.

8. The accounts of Al-Madā’inī (d. 225 AH) and ‘Utbī (228

AH) cited earlier in detail mention that it was at the behest

of Ziyād ibn Abīh (d. 53 AH), the governor of Basrah that Abū

al-Aswad undertook this job.

Accounts of Ziyād (who is also called Ziyād ibn Abī Sufyān,

Ziyād ibn Sumayyah, Ziyād ibn Amah and Ziyād ibn ‘Ubayd)

are mentioned in various books of Muslim history. None of the

following books which contain biographical accounts of Ziyād

even alludes to the fact that he had any role in this task:

i. Al-Tabaqāt

by Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230 AH)

ii. Al-Ma‘ārif

by Ibn Qutaybah (d. 276 AH)

iii. Al-Akhbār al-tiwāl

by al-Dīnwarī (d. 282 AH)

iv. Al-Istī‘āb

by Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr (d. 463 AH)

v. Tārīkh Madīnah Dimashq

by Ibn ‘Asākir (d. 571 AH)

vi. Al-Muntazim

Ibn al-Jawzī (597 AH)

vii. Al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh

by Ibn Athīr (d. 630 AH)

viii. Siyar a‘lām al-nubalā’

by al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH)

ix. Fawāt al-Wafayāt

by Muhammad ibn Shākir al-Kutbī (d. 764 AH)

x. Al-Wāfī bi al-wafayāt

by al-Safadī (764 AH)

xi. Al-Bidāyah wa al-nihāyah

by Ibn Kathīr (d. 772 AH)

xii. Al-Isābah

by Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH)

xiii. Lisān al-mīzān

by Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH)

xiv. Majma‘ al-bahrayn

by Shaykh al-Tarīhī (d. 1085 AH)

xv. A‘yān al-shī‘ah

by Sayyid Muhsin al-Amīn (d. 1371 AH)

xvi. Al-A‘lām

by al-Zarkalī (d. 1396 AH)

9. All of the chains of narration of the accounts cited under

points 2 and 3 hinge on a final Basran narrator. Is this a

mere co-incidence or does this smell of Basran bias over their

rival Kufans? There is not a single Kufan grammarian or

personality who reports that Abū al-Aswad was responsible of

putting nuqat on the masāhif. Why is this so?

In contrast to what is attributed to Abū al-Aswad al-Dū’alī’s

endeavour in putting i‘rāb on the Qur’ān, it may be noted that

sources also record on the authority of ‘Abdullāh ibn

‘Ubaydullāh ibn Abī Malaykah (d. 117 AH) with reference to

this same incident that it was at the behest of ‘Umar (rta)

that Abū al-Aswad had constituted the rules of Arabic grammar.

As per this report

a Bedouin came over to Madīnah in the reign of ‘Umar (rta) and

asked for someone who could teach him what was revealed to

Muhammad (sws). It is reported that a person taught him Sūrah

Tawbah and he read the following verse by altering the

vocalization of the last word: أَنَّ اللّهَ

بَرِيءٌ مِّنَ الْمُشْرِكِينَ وَرَسُولُهُ. He read the

last word as: رَسُولِهِ. At this the

Bedouin said: “Is God acquitted of His Messenger; if he is

acquitted of His Messenger, then I am more acquitted of the

Messenger of God.” These words of the Bedouin reached ‘Umar (rta),

who called him over and said: “Are you acquitted of the

Messenger of God.” The Bedouin replied that he came over to

Madīnah and did not have any knowledge of the Qur’ān and had

asked for someone to teach him the Qur’ān; the Bedouin

continued that a person taught him Sūrah Tawbah and read:

رَسُولِهِ أَنَّ اللّهَ بَرِيءٌ مِّنَ

الْمُشْرِكِينَ وَ; at this, he had said whether is God

acquitted of His Messenger; if he is acquitted of His

Messenger, then he [the Bedouin] is more acquitted of the

Messenger of God. At this, ‘Umar told the Bedouin that this is

not so; the Bedouin then promptly asked for an explanation.

‘Umar then read the verse as:أَنَّ اللّهَ

بَرِيءٌ مِّنَ الْمُشْرِكِينَ وَرَسُولُهُ. The Bedouin

swore by God and said that he is acquitted of those of whom

God and His Messenger are acquitted. ‘Umar then ordered that

no one except a person who has knowledge of Arabic should

teach the Qur’ān and directed Abū al-Aswad to formulate nahw

which he did so.

If the above report is true, then it can be surmised that

it had nothing to do with putting nuqat on the mushaf; it only

impelled ‘Umar (rta) to ask Abū al-Aswad to formulate the

rules of Arabic Grammar.

It may be noted that most narrators of this report are non-Basran.

Details follow:

i. Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn al-Qāsim ibn Muhammad ibn Bashshār

al-Anbārī (d. 328 AH) (born in Anbār and died in Baghdād).

ii. Muhammad ibn Yahyā ibn Abī Hazm Mihrān (d. 253 AH)

(belonged to Basrah)

iii. Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn ‘Īsā ibn Yazīd (d. 277 AH)

(belonged to Balkh).

iv. Abū Tawbah al-Rabī‘ ibn Nāfi‘ (d. 241 AH) (belonged to

Tarsūs).

v. ‘Īsā ibn Yūnus ibn ‘Amr al-Sabī‘ī (d. 287 AH) (belonged

to Kufah).

vi. ‘Abū al-Walīd Abd al-Malik ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz ibn Jurayj

(d. 150 AH) (belonged to Makkah).

vii. Abū Bakr ‘Abdullāh ibn ‘Ubaydullāh ibn Abī Malaykah

(d. 117 AH) (belonged to Makkah).

It may however be argued that there are weaknesses in this

report:

i. Ibn al-Anbārī has not specified his teacher. His words

are: “one of our companions said …(قال بعض

أصحابنا).

ii. ‘Abd al-Malik ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz ibn Jurayj is a

mudallis.

iii. Muhammad ibn ‘Īsā ibn Yazīd is also suspect. Ibn

Hibbān says that he errs a lot (yukhtī kathīr).

Ibn ‘Adī says that he steals hadīth (yasriqu al-hadīth).

10. Hamzah ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī (d. 360 AH)

and Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī (d. 380 AH)

who are the first to record the diacrtics phase on the masāhif

clearly negate that Abū al-Aswad put nuqat on the Qur’ān. This

is shown by the silence of these texts about any endeavour by

Abū al-Aswad whereas the way they mention the masāhif after

the period of ‘Uthmān (rta) entails that had Abū al-Aswad done

anything to the effect, it should have found its mention here.

Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī’s text reads:

وقد رُوى أنّ السبب في نَقْط المصاحف أن

الناس غَبَرُوا يقرءون فى مصاحف عثمان رحمة الله عليه ، نيِّفا

وأربعين سنة ، إلى أيام عبد الملك بن مروان. ثم كثر التصحيف

وانتشر بالعراق ، ففزِع الحجاَّجُ إلي كُتَّابه ، وسألهم أن

يضعوا لهذه لحروف المشْتَبِهةِ علامات. فيقال : إنّ نصرِ بن عاصم

قام بذلك ، فوضع لنَّقط أفرادا و أزواجا. وخالف بين أما كنها

بتوقيع بعضها فوق الحروف ، وبعضها نحت الحروف فَغَبَر الناس بذلك

زمانا لا يكتبون إلا منقوطا. فكان مع استعمال النقط أيضا يقع

التصحيف ، فأحدثوا الإعْجام ، فكانوا يُتْبِعون النَّقط

بالإعجام. فإذا أُغْفِل الاستقصاءُ على الكلمة فلم تُوَفَّ

حقوقَها اعترى هذا التصحيفُ ، فالتمسوا حيلةً ، فلم يقْدِروا

فيها إلا على الأخذ من أفواهِ الرجال.

It is

narrated that the reason to put nuqat on the masāhif was that

people continued to read the masāhif of ‘Uthmān (rta) for

almost forty years until [the era of] ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān

arrived. Then misreading (tashīf) of the script [of the Qur’ān]

became rampant and spread in ‘Irāq. So al-Hajjāj anxiously

turned to his scribes and asked him to devise signs for these

similar letters. It is said that Nasr ibn ‘Āsim took this

responsibility and he devised dots ones and twos and placed

them differently on them by putting some on the top and some

on the bottom of these hurūf. People stuck [to this method of

Nasr] for many years and would not write [masāhif] without

nuqat. But even after using nuqat, misreading [of the masāhif]

continued. So they invented i‘jām and used i‘jām with nuqat as

well. A slight carelessness in putting in all i‘jām with nuqat

on words again resulted in tashīf. People looked for a further

method [to secure the correct reading] but were not able to

find one except for acquiring [the Qur’ān] from the mouths of

people.

B. The Diacritics Phase

The following questions arise on the traditional account viz a

viz this phase.

1. The ascription of the insertion of diacritics to Nasr

ibn ‘Āsim is suspect. The text

of Hamzah ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī (d. 360 AH), which is the

first text to explicitly say that a lack of diacritics caused

tashīf after which these diacritics were inserted does not

even mention Nasr’s name as the one deputed to this task. The

text

of Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī (d. 382 AH) which is chronologically

the second text that explicitly says that a lack of diacritics

caused tashīf also weakly mentions Nasr’s name (the word used

is: yuqāl).

Thus none of Nasr’s students narrate this feat from him.

Al-Mizzī

has recorded the following names of his students: Bishr ibn

‘Ubayd (d. ?), Abū Sha‘thā’ Jābir ibn Zayd (d. 93 AH), Humayd

ibn Hilāl, ‘Imrān ibn Hudayr (d. 147 AH), Qatādah ibn Di‘āmah

(d. 118 AH), Mālik ibn Dīnār (d. 123 AH), Abū Sa‘d Sa‘īd ibn

al-Mirzabān al-Baqqāl (d. 140 AH approx), Abū Salamah (d. ?).

The first person to say that Nasr ibn ‘Āsim was the first

to put nuqat is Abū Hātim al-Sijistānī (d. 250 AH) as recorded

by al-Dānī.

So it is after almost two centuries that this primacy is

ascribed to him. None of Nasr’s students, as pointed out

earlier, or any one from his immediate generations has ever

reported to have said this. It can also be said with

reasonable certainty that in the first six centuries, al-Dānī

is the only person to ascribe nuqāt to Nasr. Even this primacy

of nuqat ascribed to Nasr by al-Dānī is rendered weak because

many books which mention biographical notes on Nasr are devoid

of ascribing this accomplishment to him. They include:

i. Akhbār al-nahwiyyīn al-basriyyīn

by al-Sayrāfī (d. 368

AH)

Al-Sayrāfī records on the authority of

Khālid al-Hadhdhā’ (d. 141 AH) that ‘Āsim was the first to

formulate [the principles of] Arabic.

ii. Tabaqāt al-nahwiyyīn wa lughwiyyīn

by al-Zubaydī (d. 379 AH)

Al-Zubaydī too records on the authority of

Khālid al-Hadhdhā’ (d. 141 AH) that Nasr ibn ‘Āsim

was the first to formulate [the principles of]

Arabic.

iii.

Nuzhah

al-alibbā’ by Abū al-Barkāt ibn al-Anbārī

(d. 577 AH)

Abū al-Barkāt records that Nasr ibn

‘Āsim is a jurist, a scholar of Arabic and

teacher of grammar and qirā’ah.

iv. Inbā’ al-ruwāt

by al-Qiftī (d. 624 AH)

Al-Qiftī mentions that Nasr is among the

earlierst scholars of Arabic grammar and a jurist. He also

records the report from Khālid al-Hadhdhā’ (d. 141 AH) that

Nasr ibn ‘Āsim was the first to

formulate Arabic.

v. Mu‘jam al-udabā’ by Yāqūt al-Hamawī (626 AH)

Among other minor details, Yāqūt records that Nasr was a

jurist, a scholar of Arabic and acquired the Qur’ān and nahw

from Abū al-Aswad; he initially had the same views as the

Kharijites but later abandoned them; he died in 89 AH.

vi. Tahdhīb al-kamāl

by al-Mizzī (d. 742

AH)

Al-Mizzī cites the opinion of Khalīfah ibn al-Khayyāt that

Nasr belonged to the second tabqah of the reciters of Basrah

and that as per an opinion he was the first to institute nahw.

vii. Al-Wāfī bi al-wafayāt by al-Safadī (764 AH)

Al-Safadī records almost the same information as Yāqūt

above and adds that in the opinion of Abū Dā’ūd al-Sijistānī

he was the first to formulate nahw.

viii. Tahdhīb al-tahdhīb

by Ibn

Hajar (d. 852 AH)

Ibn Hajar cites the opinion of Khalīfah ibn al-Khayyāt that

Nasr belonged to the second tabqah of the reciters of Basrah.

ix. Bughyah al-wu‘āt by al-Suyūtī (d. 911 AH)

Al-Suyūtī merely records the opinion of Yāqūt al-Hamawī

cited above.

As mentioned earlier, the above referred to books

not only do not accord any primacy of nuqat to him, they do

not even mention that Nasr had any role in this matter. This

is indeed quite strange that these biographical works on his

personality have nothing to record about him about this

alleged endeavour.

2. The first explicit ascription of Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar to the

insertion of diacritical dots to distinguish similar letters

is also suspect. The first person to mention his name is Ibn

Atiyah (d. 543 AH):

وأما شكل المصحف ونقطه فروي أن عبد الملك بن

مروان أمر به وعمله فتجرد لذلك الحجاج بواسط وجد فيه وزاد تحزيبه

وأمر وهو والي العراق الحسن ويحيى بن يعمر بذلك

As far as

the shakl and nuqat of the masāhif are concerned, it is

reported that ‘Abd al-Malik ordered for it and had it done. He

specifically deputed al-Hajjāj for this task in [the city of]

Wāsit. Al-Hajjāj expended his effort in this task and also

added divisions to the mushaf. It was while he was the

governor of Iraq that he ordered al-Hasan al-Basrī and Yahyā

ibn Ya‘mar to do this.

In other words, it is almost five centuries after the death

of Yahyā that someone has explicitly taken his name and

ascribed this endeavour to him. Moreover this report in itself

suffers from the flaw that it contradicts other reports which

say that nuqat and shakl were carried out by different

personalities. It is linguistically not possible to ascribe

the same meaning to both these words and to interpret both to

mean diacritical dots.

As far as the report that Yahyā was the first to put nuqat

on the mushaf is concerned, its earliest ascription is to

Hārūn ibn Mūsā (d. before 200 AH).

However, none of Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar’s students report this

endeavour from him. His students recorded by al-Mizzī are:

al-Azraq ibn Qays (d. after 120 AH), Ishāq ibn Suwayd (d. 131

AH), Abū Sa‘īd Thābit (d. ?), Habīb ibn ‘Atā’ (d. ?), al-Rukayn

ibn Rabī‘ (d. 131 AH), Sulaymān ibn Buraydah (d. 105 AH),

Sulaymān al-Taymī (d. 143 AH), ‘Abdullāh ibn Buraydah (d. 115

AH), ‘Abdullāh ibn Qutbah (d. ?), ‘Abdullāh ibn Kulayb (d. ?),

Abū al-Munīb ‘Ubaydullāh ibn ‘Abdullāh (?), ‘Atā al-Khurasānī

(d. 135 AH), ‘Ikramah mawlā Ibn ‘Abbās (d. 107 AH), ‘Umar ibn

‘Atā’ ibn Abī al-Khawwār (d. ?), Qatādah ibn Di‘āmah (d 117

AH) and Yahyā ibn Abī Ishāq al-Hadramī (d. 136 AH).

Even this primacy ascribed to Yahyā by Hārūn ibn Mūsā (d.

before 200 AH) is weakened due to the fact that many books

which mention biographical notes on Yahyā are devoid of

ascribing this accomplishment to him. They include:

i. Al-Tabaqāt al-kubrā by Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230 AH)

Ibn Sa‘d records that Yahyā was a

grammarian and scholar of Arabic and the Qur’ān.

ii. Marātib al-nahwiyyīn

by Abū al-Tayyib

‘Abd al-Wāhid (d. 351 AH)

Abū al-Tayyib records the statement of

Qatādah that the first person to formulate the rules of Arabic

grammar after Abū al-Aswad was Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar.

iii. Mashāhīr ‘ulamā al-amsār by Ibn Hibbān (d. 354 AH)

Ibn Hibbān says that Yahyā was a

qādī of Marw and from among the most eloquent people of his

times, a very profound scholar of Arabic and a pious person.

iv. Akhbār al-nahwiyyīn al-basriyyīn

by

al-Sayrāfī (d. 368 AH)

Al-Sayrāfī records that Yahyā added

chapters to the book of arabic grammar forumulated by Abū

al-Aswad. He also records a dialogue of his with al-Hajjāj

involving lahn.

iv. Tabaqāt al-nahwiyyīn wa lughwiyyīn by

al-Zubaydī (d. 379 AH)

Al-Zubaydī records that Yahyā learnt

Arabic grammar from Abū al-Aswad. He also records on the

authority of Khālid al-Hadhdhā’ that Ibn Sīrīn had a manqūt

mushaf on which nuqat were put by Yahyā.

v. Nuzhah al-alibbā’

by Abū al-Barkāt ibn

al-Anbārī (d. 577 AH)

Abū al-Barkāt records that Yahyā was

a scholar of Arabic and Hadīth, and would use a lot of gharīb

words in his works. He also records his dialogue with

al-Hajjāj involving lahn.

vi. Al-Muntazim

by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH)

Ibn al-Jawzī records that Yahyā was

a scholar of Arabic and the Qur’ān.

vii. Inbā’ al-ruwāt

by al-Qiftī (d. 624 AH)

Al-Qiftī records many of the details

already alluded to by his predecessors. He mentions that he

was one of the qurrā’ of Basrah. He was a qādī of

Marw and was

a scholar of the Qur’ān, Arabic grammar and the dialects of

the Arabs. He had an argument with al-Hajjāj regarding an

issue relating to lahn.

viii. Mu‘jam

al-udabā’ by Yāqūt al-Hamawī

(d. 626 AH)

Yāqūt mentions that Yahyā was a scholar of

qirā’ah, Hadīth, Fiqh, Arabic and dialects of Arabia.

ix. Wafayāt al-a‘yān

by Ibn Khallikān (d.

681 AH)

Ibn Khallikān mentions that Yahyā was a

scholar of the Qur’ān, Arabic grammar and the dialects of

Arabia, and that he had learnt Arabic grammar from Abū

al-Aswad. He also records a dialogue of his with al-Hajjāj

involving lahn.

x. Bughyah al-wu‘āt

by

al-Suyūtī (d. 911 AH)

Al-Suyūtī records that Yahya learnt

Arabic grammar from Abū al-Aswad and was appointed the qādī of

Khurasan by Qutaybah ibn Muslim.

The above referred to books not only do not accord any

primacy of nuqat to him, they do not even mention that Yahyā

had any role in inseting nuqat on the masāhif or that Yahyā

was summoned by al-Hajjāj for this purpose even though as

referred to earlier some of them record a dialogue between

Yahyā and al-Hajjāj about lahn.

This is indeed quite strange that such early biographical

works on his personality have nothing to record about him

about this alleged endeavour.

3. Ibn Atiyah (d. 543 AH),

al-Qurtubī (d. 671 AH),182

Ibn al-Jazzī Kalbī (d. 757 AH)

and Ibn Kathīr (d. 774 AH)

mention that al-Hajjāj had deputed al-Hasan al-Basrī (d. 110

AH) as well for putting nuqat on the masāhif together with

Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar.

The following books contain biographical accounts of al-Hasan

ibn al-Hasan al-Basrī but do not mention that he had any role

in putting nuqat on the masāhif.

i. Al-Tabaqāt

by Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230 AH)

ii. Al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr

by al-Bukhārī d. (256 AH)

iii. Tārīkh Wāsit

by Aslam ibn Sahl al-Wāsitī (d. 264 AH)

iv. Al-Ma‘ārif

by Ibn Qutaybah (d. 276 AH)

v. Al-Ma‘rifah wa al-tārīkh

by al-Fasawī (d. 277 AH)

vi. Akhbār al-qudāt

by Muhammad ibn Khalaf ibn Hayyān (d. 306 AH)

vii. Al-Muntazim

by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH)

viii. Wafayāt al-a‘yan

by Ibn Khallikān (d. 681 AH)

ix. Tahdhīb al-kamāl

by al-Mizzī (d. 743 AH)

x. Siyar a‘lām al-nubalā’

by al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH)

xi. Al-Wāfī bi al-wafayāt

by al-Safadī (764 AH)

It may be of further interest to note contradictory reports

ascribed to al-Hasan: some say that al-Hasan approved of

putting nuqat on the masāhif, while others report the

opposite.

4. Hamzah ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī (d. 360 AH)

and Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī (d. 380 AH)

who are the earliest to record the diacritics phase mention

that it was al-Hajjāj who was primarily responsible for

carrying out the remedial measures for stopping tashīf.

Similarly, Ibn Atiyah (d. 543 AH),

al-Qurtubī (d. 671 AH),

Ibn al-Jazzī Kalbī (d. 757 AH)

and Ibn Kathīr (d. 774 AH)

also mention al-Hajjāj was deputed for this task and further

mention that ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān, the then caliph of the

Muslims deputed him for this purpose. They say that he had

asked al-Hajjāj to put nuqat and shakl on the masāhif.

Now it is known that both al-Hajjāj ibn Yūsuf and ‘Abd al-Malik

ibn Marwān are two celebrated personalities of the Umayyad

caliphate. Their achievements and feats have been recorded in

detail by all historians. It is quite strange that a vast

majority of historians do not record any such achievement by

either of them.

Following is a brief survey of both these personalities in

early and medieval history works:

I ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān

i. Al-Tabaqāt

by Ibn Sa‘d (d. 230 AH)

ii. Al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr

by al-Bukhārī d. (256 AH)

iii. Tārīkh Wāsit

by Aslam ibn Sahl al-Wāsitī (d. 264 AH)

iv. Al-Ma‘ārif.

by Ibn Qutaybah (276 AH)

v. Tārīkh

by al-Ya‘qūbī (d. 292 AH)

vi. Al-‘Iqd al-farīd

by Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih (d. 328 AH)

vii. Kitāb al-wuzarā wa al-kuttāb

by Al-Jahshiyarī (d. 331AH)

viii. Al-Bad’ wa al-tārīkh

by al-Maqdisī (d. 355 AH)

ix. Tārīkh Baghdād

by al-Khatīb al-Baghdādī (d. 463 AH)

x. Tārīkh Madīnah Dimashq

by Ibn ‘Asākir (d. 571 AH)

xi. Al-Muntazim

by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH)

xii. Tahdhīb al-kamāl

by al-Mizzī (d. 742 AH)

xiii. Siyar a‘lām al-nubalā’

by al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH)

xiv. Al-Wāfī bi al-wafayāt

by al-Safadī (764 AH)

xv. Al-Bidāyah wa al-nihāyah

by Ibn Kathīr (d. 772 AH)

xvi. Tahdhīb al-tahdhīb

by Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH)

II Al-Hajjāj ibn Yūsuf al-Thaqafī

i. Tārīkh Wāsit

by Aslam ibn Sahl al-Wāsitī (d. 264 AH)

ii. Al-Ma‘ārif

by Ibn Qutaybah (276 AH)

iii. Kitāb al-wuzarā wa al-kuttāb

by Al-Jahshiyarī (d. 331AH)

iv. Al-Bad’ wa al-tārīkh

by by al-Maqdisī (d. 355 AH)

v. Tārīkh Madīnah Dimashq

by Ibn ‘Asākir (d. 571 AH)

vi. Al-Muntazim

by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH)

vii. Al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh

by Ibn Athīr (d. 630 AH)

viii. Tahdhīb al-kamāl.

by al-Mizzī (d. 742 AH)

It may be noted that perhaps the first historian to say that

al-Hajjāj was responsible for this endavour is Ibn Khallikān

(d. 681 AH).

However, his source is the text of Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī

already referred to above. Similarly, al-Safadī (764 AH)

also refers to this on the basis of Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī. Ibn

Kathīr (d. 772 AH)

does say that during the days of al-Hajjāj, the nuqat were put

on the masāhif and does not mention any source of this

statement.

5. The texts of Hamzah ibn al-Hasan al-Asbahānī (d. 360 AH)

and Abū Ahmad al-‘Askarī (d. 380 AH)

say that Nasr ibn ‘Āsim was the originator of diacritics on

similar letters. This contradicts the following information.

Ibn ‘Abbās is reported to have said:

أول من كتب بالعربية ثلاثة رجال من بولان

وهي قبيلة سكنوا الأنبار

وأنهم اجتمعوا فوضعوا حروفا مقطعة

وموصولة وهم مرار بن مرة وأسلم بن سدرة وعامر بن جدرة ويقال مروة

وجدلة فأما مرامر فوضع الصور وأما أسلم ففصل ووصل وأما عامر فوضع

الإعجام

The first

ones to write Arabic were three men from Būlān which is a

tribe that lived at al-Anbār; they got together and coined the

letters – both in their connected and disconnected forms.

These three were: Marāmir ibn Murrah, Aslām ibn Sidrah and

‘Āmir ibn Jadrah (also: Marwah / Jadalah). As for Marāmir, he

conceived the forms (suwar)) of the letters, Aslam their

separations and linkages (fasl and wasl) while ‘Āmir invented

the diacritics (i‘jām).

Al-Qalqashandī

says that the diacritics were invented at the time of the

letters because it is very unlikely that letters which

resemble one another should be devoid of them. Al-Kurdī,

Jumu‘ah

and Hifnī

also say that they were invented at the time of the letters

themselves. Salāh al-Dīn Munajjid

and ‘Abd al-Sabūr Shahīn

surmise that it was not that Nasr and Yahyā originated them

because their existence is found in earlier writings.

Thus the earliest dated Arabic document (recently

re-deciphered by Healy and Smith) corresponding to 267 AD

shows dots on dhāl, rā and shīn.

‘Alī ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān in an article (translated from

Arabic by Robert Hoyland) has given tracings of the following

writings which depict the use of diacritical dots on various

letters in the first century.

Among them, the following are clearly well before the time

dots were allegedly invented by Nasr.

i. Papyrus of Ahnus housed in Vienna National Library (22 AH).

Diacritical dots appear on the letters: sha, za, dha, kha, ja

and na.

ii. Zuhayr inscription in Saudi Arabia (24 AH). Diacritical

dots appear on the letters: nūn (on three occasions), za (on

two occasions), dha, ta, fa and sha.

iii. Al-Khanaq dam inscription near Madīnah (40-60 AH). A

diacritical dot appears on the letter ta.

iv. Wadi Sabil inscription near Najran (46 AH). A diacritical

dot appears on the letter ba.

v. Mu‘āwiyah dam inscription near Tā’if (58 AH). Diacritical

dots appear on the letters: ba (on four occasions), na (on

four occasions), ya (on four occasions), tha (on two

occasions), ta (on two occasions)

Mirza,

in a recent PhD dissertation has shown the existence of a

diacritical dot on the letter na (occurring twice) in the

Prophet’s letter (6 / 8 AH) to al-Mundhir ibn al-Sāwā,

governor of Bahrayn. As such, this is perhaps the earliest

occurrence of a diacritical dot on documents discovered so

far.

Gruendler has also pointed out many early texts which have

diacritical dots. The following are clearly before the period

of the alleged invention of diacritics by Nasr:

i. Entagion (P. Colt no 60). This consists of thirteen papyri

and most of them are entagia (announcements of taxes owed by a

local community). As specified by her, it is written by Abū

Sa‘īd and dates 54 AH/ 674 CE and several diacritics appear on

ba, ta, za and qāf.

ii. Tax Receipt (57 AH) confirming payment of an amount of 108

dīnār and 19 qīrāt for land tax. Diacritics appear on ba, na

and some other letters.

iii. Receipt for delivery of wheat dated to the second half of

the first Islamic century (643-670 CE). Diacritical dots are

visible on za, qāf and na.

iv. Letter from ‘Abd al-‘Azīz ibn Marwān (governor of Egypt

65-85 AH) to the inhabitants of Ihnās (Herakleopolis).

Diacritics appear on za, ba, dha, na.

Thus while referring to this established information that

diacritics were invented with the letters, here is some

further corroboratory evidence:

It is recorded by al-Farrā’ (d. 206 AH):

حدثنا محمد بن

الجهم ، قال حدثنا الفراء ، قال حدثنى سفيان بن عُيَيْنة رفعه

إلى زيد ابن ثابت قال : كُتِب فى حَجَر سرها ولم نس وانظر إلي

زيد بن ثابت فنقط على الشين والزاى أربعا وكتب (يتسنه) بالهاء

Sufyān ibn ‘Uyaynah reports while connecting the chain of

narration to Zayd ibn Thābit: Zayd wrote on stone the

following words: سرها and

ولم نس and وانظر

إلي. He put four dots on shīn and zā and wrote the word

يتسنwith a hā [ie.]

يتسنه.

Al-Khatīb

al-Baghdādī (d. 463 AH) records:

انا محمد بن علي بن الفتح الحربي نا عمر بن

احمد الواعظ نا محمد ابن مخلد بن حفص العطار نا رجاء بن سهل

الصاغاني نا ابو مسهر عن سعيد ابن عبد العزيز التنوخي عن قيس بن

عباد عن محمد بن عبيد بن اوس الغساني كاتب معاوية قال حدثني ابي

قال كتبت بين يدي معاوية كتابا فقال لي يا

عبيد ارقش كتابك

فإني كتبت بين يدي رسول الله كتابا

رقشته قال قلت وما رقشة يا امير المؤمنين قال اعط كل حرف ما

ينوبه من النقط

‘Ubayd ibn

Aws al-Ghassānī said: “I wrote a letter in the presence of

Mu‘āwiyah. He said to me: ‘O ‘Ubayd adorn your letter because

I wrote a letter in the presence of the Messenger of God (sws)

which I had adorned [raqashtuhū.’] I asked: ‘What does

raqshatun mean O leader of the believers!’ He replied: ‘Give

to each letter the dots it deserves.’”

C. The Second Vocalization Phase

The following questions arise on the traditional account viz a

viz this phase.

1. In the second vocalization phase, to al-Khalīl ibn Ahmad

al-Farāhīdī (d. 170 AH) is attributed vocalization marks which

were the forerunners to the vocalization dashes we find today.

None of his students narrate this feat from him. According

to al-Mizzī,

his students are: Ayyūb ibn al-Mutawakkil al-Basrī (d. 200

AH), Badal ibn al-Muhabbar, Hammād ibn Zayd (d. 179 AH), Dā’ūd

ibn al-Muhabbar (d. 207 AH), Sībawayh (‘Amr ibn ‘Uthmān ibn

Qanbar) (d. 194 AH), ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Qarīb al-Asma‘ī (d. 216

AH), ‘Alī ibn Nasr al-Jahdamī (d. 250 AH), ‘Awn ibn ‘Umārah

(d. 212 AH), al-Mu’arrij ibn ‘Amr al-Sadūsī (d. 195 AH), Mūsā

ibn Ayyūb, al-Nadr ibn Shumayl (d. 203 AH), Hārūn ibn Mūsā al-A‘war

(before 200 AH), Wahb ibn Jarīr ibn Hāzim (206 AH) and Yazīd

ibn Murrah (d.

This poses a question mark on the ascription of this feat

to al-Khalīl.

2. The following biographical accounts in Muslim history

books are devoid of any such feat by al-Khalīl ibn Ahmad al-Farāhīdī

(d. 170 AH) in spite of the fact that many of them record him

as the inventor of the discipline of ‘urūd (Arabic prosody)

and the first person to compile a dictionary of Arabic (Kitāb

al-‘ayn):

i. Tabaqāt fuhūl al-shu‘arā’

by Muhammad ibn Sallām al-Jumahī (d. 230 AH)

ii. Al-Tārīkh al-Kabīr

by al-Bukhārī d. (256 AH)

iii. Al-Ma‘ārif

by Ibn Qutaybah (276 AH)

iv. Al-‘Iqd al-farīd

by Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih (d. 328 AH)

v. Marātib al-nahwiyyīn

by Abū al-Tayyib ‘Abd al-Wāhid (d. 351 AH)

vi. Akhbār al-nahwiyyīn al-basriyyīn

by Sa‘īd al-Sayrafī (d. 368 AH)

vii. Tabaqāt al-nahwiyyīn

by al-Zubaydī (d. 379 AH)

viii. Al-Fihrist

by Ibn Nadīm (d. 380 AH)

ix. Nuzhah

al-alibbā’

by Abū al-Barkāt

ibn al-Anbārī (d. 577 AH)

x. Al-Muntazim

by Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH)

xi. Inbā’

al-ruwāt

by Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qiftī (d. 624 AH)

xii. Mu‘jam al-udabā’260

by Yāqūt al-Hamawī (626 AH)

xiii. Tahdhīb al-asmā’ wa al-lughāt261

by al-Nawawī (d. 676 AH)

xiv. Wafayāt al-a‘yan262

by Ibn Khallikān (d. 681 AH)

xv. Tahdhīb al-kamāl263

by al-Mizzī (d. 742 AH)

xvi. Tārīkh al-Islām264

by al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH)

xvii. Siyar a‘lām al-nubalā’265

by al-Dhahabī (d. 748 AH)

xviii. Al-‘Ibar fī khabar-i man ghabar266

by al-Dhahabī

xix. Al-Wāfī bi al-wafayāt267

by al-Safadī (764 AH)

xx. Mir’āt al-jinān268

by Abū Muhammad al-Yafi‘ī (d. 768 AH)

xxi. Al-Bidāyah wa al-nihāyah269

by Ibn Kathīr (d. 772 AH)

xxii. Subh al-a‘shā

by al-Qalqashandī (d. 791 AH)

xxiii. Muqaddimah by Ibn Khaldūn

(d. 808 AH)

xxiv. Bulghah

by al-Fayrūzābādī (d. 810 AH)

xxv. Ghāyah al-nihāyah

by Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 833 AH)

xxvi. Tahdhīb al-tahdhīb

by Ibn Hajar (d. 852 AH)

xxvii. Bughyah al-wu‘āt

by al-Suyūtī (d. 911 AH)

xxviii. Shadharat al-dhahab

by ‘Abd al-Hayy al-Hanbalī (d. 1089 AH)

xxix. Tanqīh al-maqāl

by al-Maqāmānī (d. 1351 AH)

xxx. Al-A‘lām

by al-Zarkalī (d. 1396 AH)

The following works however cite that al-Khalīl was

responsible for this endeavour:

i. Al-Muhkam

by al-Dānī (d. 444 AH). He records that Abū al-Hasan ibn

Kaysān reported this from Muhammad ibn Yazīd al-Mubarrad (d.

285 AH)

ii. Alif bā’

by al-Balawī (d. 604 AH)

iii. Al-Wasīlah ilā Kashf al-‘aqīlah

by al-Sakhāwī (d. 643 AH)

iv. Al-Itqān

by al-Suyutī (d. 911 AH)

Following are some of the contemporary works that refer to

this endeavour of al-Khalīl:

i. Al-Sabīl ilā dabt kalimāt al-tanzīl

by Ahmad Muhammad Abū Zaytahār (d. 1413 AH)

ii. Hayāt al-lughah al-‘arabiyyah

by Hifnī Bik Nāsif (d. 1337 AH)

iii. Qissah al-kitābah al-‘arabiyyah

by Ibrāhīm Jumu‘ah

Given the paucity of mention in overwhelmingly large number

of sources, the ascription of this endeavour to al-Khalīl

seems to stand on slippery grounds.

D. Manuscript Evidence

A little deliberation on the traditional accounts of the

development of vocalization and diacritics in Qur’ānic

orthography shows that the vocalization of the mushaf was

completed first. Once this was done, only then came the phase

of putting diacritics to distinguish similar graphemes.

Thus these accounts entail that there should be some early

Qur’ānic masāhif even in partial which are fully vocalized

with red dots but have no black dots as diacritic marks to

distinguish letters because the diacritical phase came almost

three decades after the vocalization phase. Similarly there

should be no masāhif which only have black dots to mark

diacritics and no red dots to mark vocalization because the

latter preceded the former.

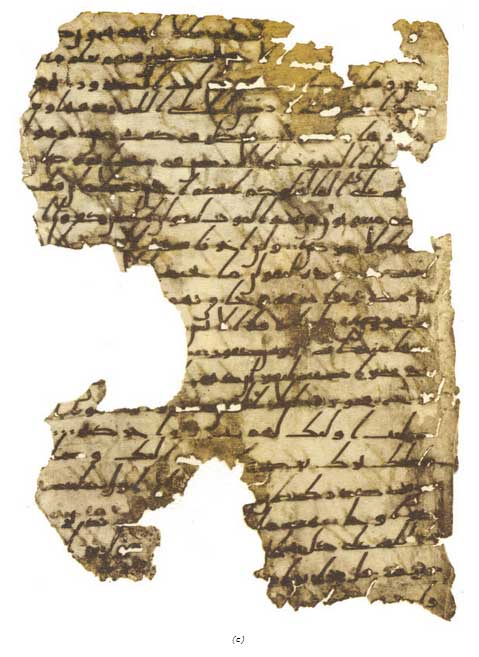

On the contrary, empirical evidence shows the reverse: the

earliest Qur’anic manuscripts (hijāzī manuscripts) and some of

the early Kufic ones also

do have black dots to mark diacritics even though sparingly;

they do not have red dots for vocalization. No Hijāzī

manuscript has thus far been discovered which has only red

dots to mark vocalization.

Here are some examples:

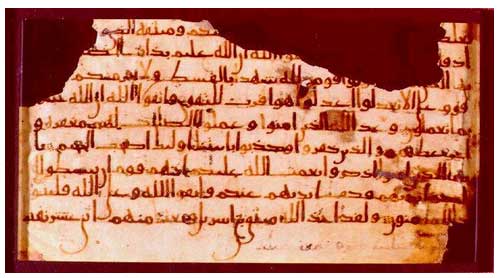

i. Sūrah Ibrāhīm, verses 19-44. Location: not known. 1st

century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī. No vocalization but

diacritics present sparingly in the form of dots and angled

dashes.

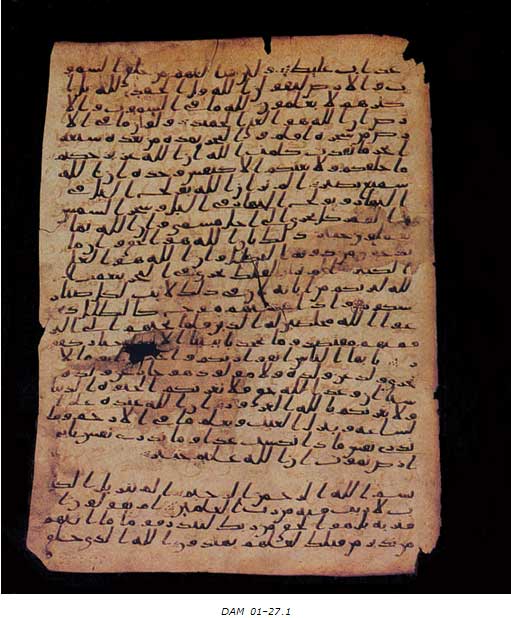

ii.

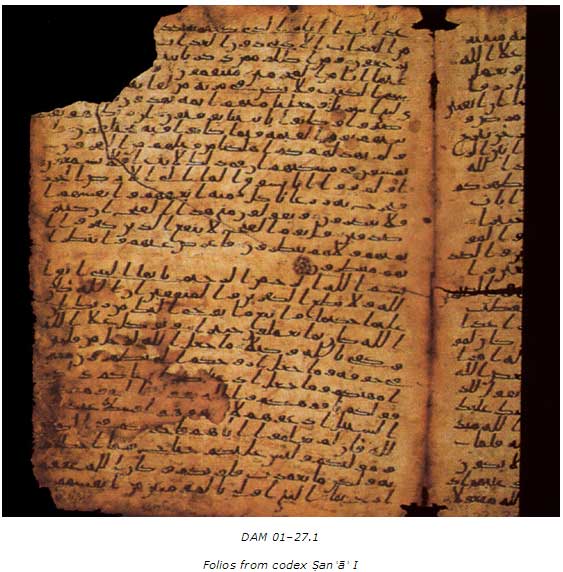

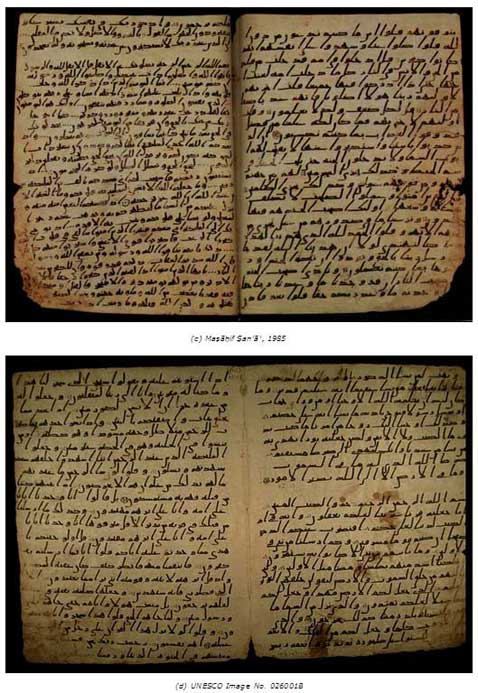

Codex Ṣan‘ā DAM 01-27.1. 1st century hijrah. The script

is Hijāzī. Location: al-Maktabah al-Sharqiyyah and Dār al-Makhṭūtāt,

Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. Also at the David Collection, Copenhagen, and

other private collections. Miscellaneous verses. These

palimpsests have a few diacritical marks with no vocalization

and sūrah titles.

In a recent study of this codex, Sadeghi has concluded that

its scriptio inferior belongs to the period of the companions

of Muhammad (sws), whilst its scriptio superior belongs to the

ʿUthmānic tradition.

iii. No number. Sūrah An‘ām, verses 5-20. 1st century hijrah.

The script is Hijāzī. Location: Maktabah al-Jāmi‘ al-Kābir,

San‘ā (Yemen). Diacritics present.

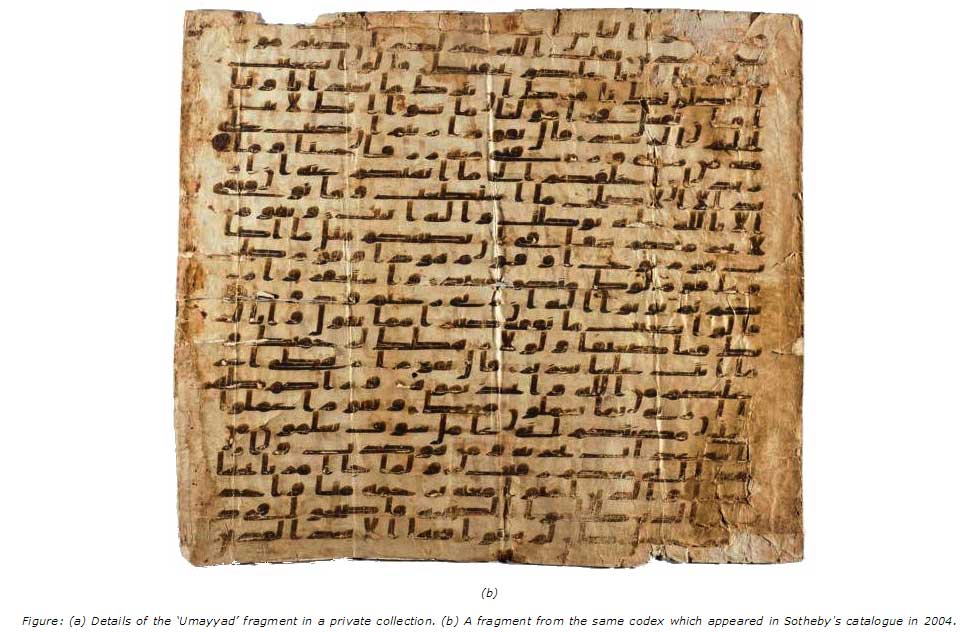

iv. Side A: Sūrah Muddaththir, verses 1-27; Side B: Sūrah

Muddaththir, verses 34-56. The Sotheby’s 2004 fragment

contains Sūrah Hūd, verses 73-95. 1st century hijrah.

Location: A private collection in London. Script is Kufic.

Consonants are sparsely differentiated.

v. Arabe 328a. Miscellaneous verses. 1st century hijrah. The

script is Hijāzī. Location: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris;

Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; Nasser D.

Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London. Occasional

diacritical strokes. There is no vocalization. Reading of Ibn

‘Āmir.

vi. MS. Or. 2165. Miscellaneous verses. 1st century hijrah.

The script is Hijāzī. Studied by Instisar Rabb and reassigned

the reading of Hims. Location: British Library, London UK. The

consonants are frequently differentiated by dashes.

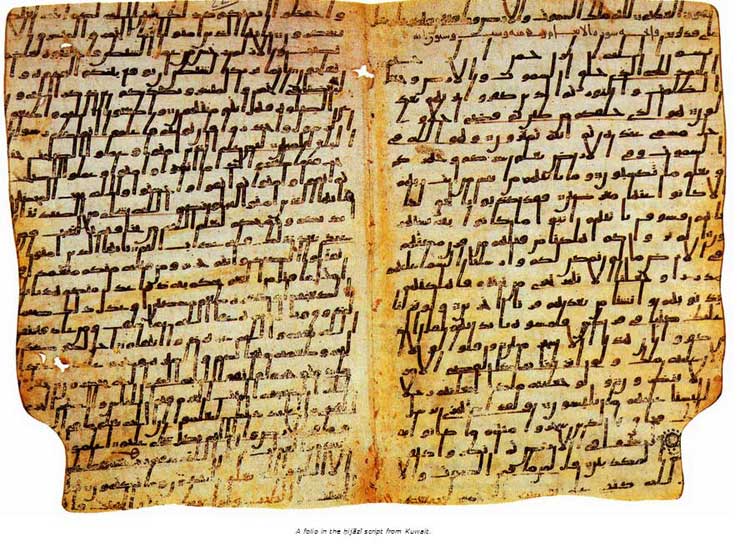

vii. LNS 19

CAab. Surah Mā’idah, verse 89 to Sūrah An‘ām, verse 12. 1st

century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī. Location: Dār al-Athar

al-Islāmiyyah, Kuwait. This manuscript bears a striking

resemblance to the British Museum

Ms. Or. 2165. The consonants are frequently differentiated

by dashes.

viii.

1611-mkh235. Sūrah Mā’idah, verses 7-12. 1st century hijrah.

Script is early kufic. Location: Bayt al-Qur’ān, Manama,

Bahrain. Diacritics present.

ix. Ms. Qāf 47. Miscellaneous Verses. 1st century hijrah. The

script is Hijāzī. Location: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin,

Germany, and Dār al-Kutub al-Misriyyah, Cairo. The consonants

are differentiated by dashes.

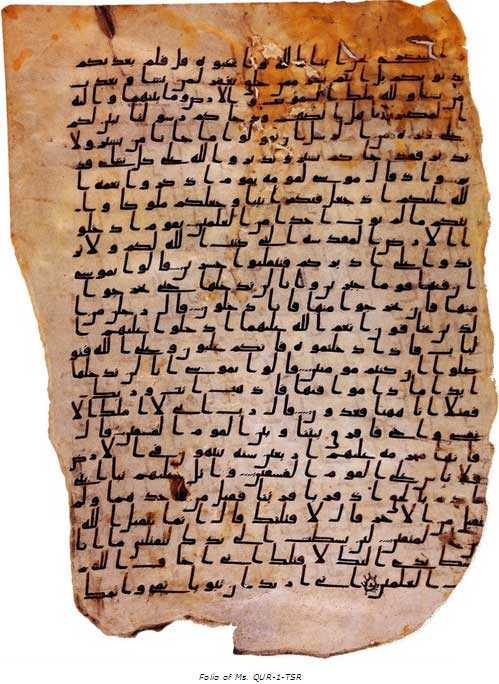

x. QUR-1-TSR. Sūrah Mā’idah, verses 18-29. 1st century hijrah.

The script is Hijāzī. Location:

Tareq Rajab Museum, Kuwait. The consonants are frequently

differentiated by dashes.

xi. Codex Ṣan‘ā DAM 01-25.1. Miscellaneous verses. 1st

century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī. Location: Dār al-Makhtūtāt,

Ṣan‘ā, Yemen. There are few diacritical marks.

xii. DAM 01-29.1 Miscellaneous verses. 1st century hijrah. The

script is Hijāzī. Location: Dār al-Makhtutāt, Ṣanā, Yemen.

There are few diacritical marks.

xiii. M. 1572. Miscellaneous verses. 1st century hijrah. The

script is Hijāzī. Location: University of Birmingham,

Birmingham, UK. The consonants are differentiated by dashes.

The muṣḥaf is partly vocalized with red dots by a later (?)

hand.

xiv. No number. 1st century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī.

Location: Not known. Diacritical marks, where present,

consists of oval dots or angled dashes.

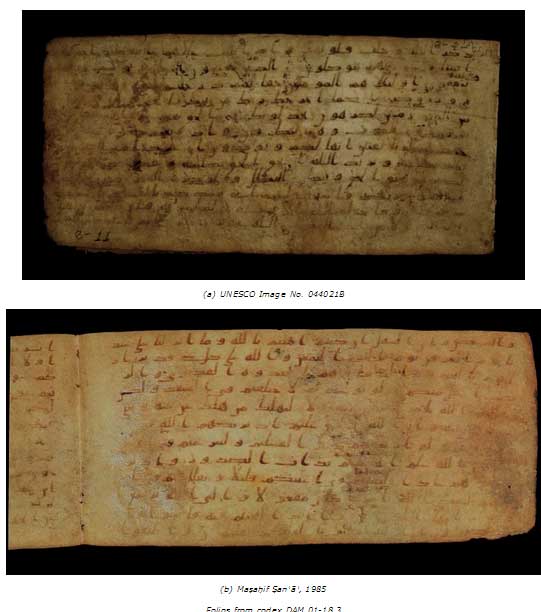

xv. DAM 01-28.1. Miscellaneous verses. 1st – 2nd century

hijrah. The script is Hijāzi. Location: Dār al-Makhtūtāt,

Ṣan‘ā, Yemen. Diacritical marks are frequent.

xvi. Codex Ṣan‘ā DAM 01-18.3. Sūrah Anfāl, verses 2-11 and

41-46. 1st – 2nd century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī.

Location: Dār al-Makhtūtāt, Ṣan‘ā, Yemen. Few diacritical

marks.

xvii. Codex Ṣan‘ā DAM 01-30.1 Miscellaneous verses. 2nd

century hijrah. The script is Hijāzī. Location: Dār al-Maktūtāt,

Ṣan‘ā, Yemen. Few diacritical marks.

xviii. Codex Ṣan‘ā DAM 01-29.2. Miscellaneous verses. 2nd

century hijrah. The script is kufic. Location: Dār al-Makhtūtāt,

Ṣanā, Yemen. Diacritical marks are sparsely distributed.

It may be of further interest to note that Giorgio Levi Della

Vida (d. 1967) has published one of the earliest partial

Qur’ān masāhif on parchment. It belongs to the first century

and is found in the Vatican Library. It begins with the fourth

verse of Sūrah Hūd. Diacritical dots are apparent.

IV. Conclusion

In the light of

this analysis, it can be gathered that the way traditional

Muslim sources ascribe the introduction of vocalization and

diacritics to certain personalities in the first century of

Islam is not sound. The roles alleged to have been played by

Abū al-Aswad al-Du’alī, Nasr ibn ‘Āsim and Yahyā ibn Ya‘mar

cannot be established historically through reliable means.

Empirical evidence also negates the traditional Muslim

account. Even the alleged development made by al-Khalīl ibn

Ahmad al-Farāhīdī in vocalization symbols stands on slippery

ground.

However, as far

as the scheme of vocalization and diacritics (both initially

represented by dots) is concerned, it does clearly appear in

the early manuscripts discovered. So the question arises on

the origin of this scheme. Who was responsible for it?

As far as the

dotting of similar letters is concerned, it can be said with

reasonable certainty that these dots were invented with the

invention of the alphabet. They were however sparingly used in

writing the Qur’ān since the reliance was primarily on oral

transmission. It seems that as written Qur’āns became more

pervasive to cater for the need of converts and for the

teaching of children etc the sparingly used dots gradually

gave way to dots being used everywhere on the letters that

needed it. The scheme of dotting similar letter thus would not

require that its originator be researched into and it be

ascribed to particular individuals.

As far as

vocalization is concerned, it seems quite plausible that this

is something which perhaps the Arabs borrowed from the Syriac

tradition to which they were exposed. Versteegh (b. 1947)

has pointed out the striking correlation between the Arabic

signs fatha, kasrah and dammah and the Syriac signs pētāhā

(opening), hēbāsā (pushing) and ēsāsā (contraction). In all

probability, the Syriac signs were also represented by

sublinear and supralinear dots.

When exactly was this dot notation introduced in Qur’ānic

manuscripts cannot be said with certainty. Manuscript studies

may help us ascertain this fact.

It would thus

be better to give up the long-standing view of ascribing to

certain personalities the origination of nuqat meant both for

vocalization and diacritics. Similarly, if it is correct to

conclude that al-Khalīl ibn Ahmad al-Farāhīdī had no role in

the second vocalization phase in which the dot notation was

changed to the dash/stroke notation, then the question may be

posed: Who was responsible for this? To the best of my

knowledge, the available material on this subject does not

give a clue to the answer of this question. However, this

development may have been the handiwork of an innovative

scribe who deemed black dotted notation for diacritics and the

red dotted notation of vocalization were becoming cumbersome

for the scribes and confusing for the readers. His idea

obviously was then picked up by many others. However, this is

merely a conjecture and at the moment lacks historical

corroboration.

________________________

|