Preface

Luleå is a city in the North of Sweden. During the month of

June, there are days in Luleå when the dawn time is 00:51 AM and the sunset is

11:43 PM. When the month of Ramadān falls in June, those among the minority

Muslims of Luleå who can bear it, fast for about 23 hours a day. They have less

than 2 hours to break their fast, do their obligatory and supererogatory prayers

and have their suhūr before starting another day of about 23 hours of fasting.

They do this due to the understanding that based on verse 2:178 of the Qur’ān

they are expected by the Almighty to fast that long unless they are physically

incapable of that. This is while at the same time their fellow Muslims in the

Muslim countries are fasting for fourteen or fifteen hours per day. The popular

advice for them is that if they cannot tolerate these long hours, they need to

fast during other times of year.

Kristoffer Törnmalm writes in Swedish Daily Paper:

It will be a challenge. 30 years ago there were not this

many Muslims living here in Sweden and especially not up in the North. Today it

is a problem that touches more people. … For us the fasting takes around 20

hours. Many people think it will be hard. But it is always worst in the first

days, then it usually gets better.

But for the moment there is no agreement to rely upon. …

There is nobody who is certain on how to do. It is partly because the persons

who have the authority in the Muslim world have difficulties in understanding

how it is in practice, it is basically impossible to understand.

This article is written solely to help with inquiries

similar to the above.

Introduction

This articles aims to address a contemporary issue with

regards to fasting that is specifically relevant to Muslims who live in certain

geographical places like Northern Europe. After explaining and illustrating the

issue, first the more popular and dominant view will be presented and discussed.

This view will then be critically analyzed by comparing it with a less popular

and less dominant view. The article ends with some concluding remarks where the

advantages and disadvantages of each view are discussed and suggestions are

given.

The inquiry that is discussed in this article is related to

places where there is proper day and night within 24 hours, however the day is

extremely long at certain times of the year. The areas where there is no proper

day or night within 24 hours is not the subject of this article.

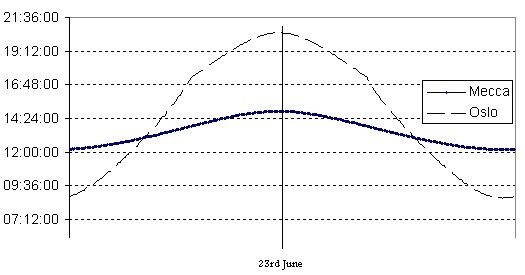

It is a well-known fact that in countries above the 50

degrees latitude, the fasting time during the summer is extremely long. To look

at an example, Oslo in Norway experiences summer time days of more than 20

hours. It is interesting to compare the shortest and longest fasting hours

between the two cities of Mecca and Oslo. The figure below summarises the

difference:

The above figure illustrates the change in fasting time

throughout the year for Mecca and Oslo. The thick, continuous line represents

the length of fasting throughout the year in Mecca while the non-continuous thin

line represents the same for Oslo, Norway. Some descriptive analysis follows:

|

|

Shortest Fasting Time (hours) |

Longest Fasting Time (hours) |

Difference between the shortest and the longest fasting time in each city |

|

Makkah |

12:11 |

14:55 |

2:44 |

|

Oslo |

8:43 |

20:31 |

11:48 |

|

Difference between the two cities |

3:28 |

5:36 |

9:04 |

According to this calculation for year 2010, the shortest

fasting times for Makkah and Oslo were respectively 12 hours and 11 minutes, and

eight hours and 43 minutes. This happened on 21st of December 2010. The longest

fasting times for Makkah and Oslo were respectively 14 hours and 55 minutes, and

20 hours and 31 minutes. This happened on 23rd July 2010. While in Makkah

fasting time changes only two hours and 44 minutes thought out a year, in Oslo

it changes by 11 hours and 48 minutes. The difference between the longest

fasting time in Makkah and Oslo is five hours and 36 minutes.

The obvious problem here is the very long fasting days of

summer in Oslo, that is representative of many other countries in the world with

similar or even more extreme conditions. While in Makkah, the original centre of

Islam, and in most other Muslim countries, people fast around 14 hours or so

during the summer time; in some places in the world, like Oslo, the minority

Muslim population (which is already disadvantaged by the lack of social support

for their ritual fasting), needs to fast more than 20 hours per day that is

about 1.5 times compared to fasting times of other Muslims.

The reader should not think that the above is a very

extreme condition. Cities like Luleå in Sweden experience fasting time of about

23 hours per day during the summer.

The continuous fasting for 20 to 23 hours per day for up to

thirty days makes fasting during summer a challenge in places like Oslo and

Luleå, which, for some Muslims, is difficult to manage. What makes this more

difficult is that during the less than 4 hours (or about an hour in case of

Luleå) that is available between sunset and dawn, the person breaks the fast,

offers maghrib and ‘ishā prayers, perhaps wishes to participate in what is known

as tarāwīh prayers and then also needs to have suhūr before starting another

fast.

It is only natural to see many inquiries arising from this

situation. People rightly want to know what their religious duty is when they

face such long fasting hours. Some of these inquiries very rightly and

innocently sound quite desperate:

Several Muslim associations in the North of Sweden have

taken contact with among others the Islamic Association and asked how to cope

with the feast when it occurs in the Summer. Kabir Marefat, President of the

Islamic Association in Luleå, has contacted several learned Muslims both in

Sweden and in Saudi Arabia and asked for interpretations of the fasting rules

that may facilitate the fasting of the Luleå Muslims.

The Dominant View

In answering inquiries like the above, the popular view

seems to be to keep fasting, no matter how long the day is, unless it is beyond

the capacity of an individual. For instance the following statement is issued as

the statement of The Council of Senior Scholars in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia:

With regard to the timings of

their fast in Ramadān, those who are accountable should refrain from food, drink

and everything else that invalidates the fast each day of Ramadān, from the time

of dawn until sunset in their countries, so long as the night can be

distinguished from the day, and when day and night together add up to

twenty-four hours. It is permissible for them to eat, drink, have intercourse,

etc during the night only, even if it is short. The sharī‘ah of Islam is

universal and applies to all people in all countries. Allah says (interpretation

of the meaning):

And eat and drink until the

white thread (light) of dawn appears to you distinct from the black thread

(darkness of night), then complete your fast till nightfall. (2:187)

In answering a similar question, the Centre of Religious

Statement of Saudi Arabia, Al-Lajnah al-Dā’imah li al-Buhūth al-‘Amaliyyah wa

al-Iftā chaired by ‘Abd al-‘Azīz ibn ‘Abdullāh ibn Bāz at the time, has written:

قد خاطب الله المؤمنين بفرض الصيام فقال تعالى: { يَا أَيُّهَا

الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا كُتِبَ عَلَيْكُمُ الصِّيَامُ كَمَا كُتِبَ عَلَى الَّذِينَ مِنْ

قَبْلِكُمْ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَتَّقُونَ } وبين ابتداء الصيام وانتهاءه فقال تعالى: {

وَكُلُوا وَاشْرَبُوا حَتَّى يَتَبَيَّنَ لَكُمُ الْخَيْطُ الْأَبْيَضُ مِنَ

الْخَيْطِ الْأَسْوَدِ مِنَ الْفَجْرِ ثُمَّ أَتِمُّوا الصِّيَامَ إِلَى اللَّيْلِ

} ولم يخصص هذا الحكم ببلد ولا بنوع من الناس، بل شرعه شرعا عاما، وهؤلاء المسئول

عنهم داخلون في هذا العموم

Verily God has addressed

(all) believers about the obligation of fasting so the Almighty says:

“Believers! Fasting has been made obligatory upon you as it was made upon those

before you so that you become fearful of God,” and the beginning and the end of

fasting is explained as the Almighty says: “And eat and drink until the white

thread of the dawn is totally evident to you from the black thread of night;

then complete the fast till nightfall,” and this directive is not specific to

any city or any type of people, rather, it is made as a general rule, and the

people who are the subject of the question (i.e. those living in places where

night during summer lasts only three hours) are included in this general rule.

Another similar view:

… every responsible adult

Muslim who is present when Ramadān comes is obliged to fast, no matter whether

the day is short or long. If a person is unable to complete a day’s fast, and

fears that he may die or become ill, he is permitted to eat just enough to keep

his strength up and keep himself safe from harm, then he should stop eating and

drinking for the rest of the day, and he has to make up the days he has missed

later on, when he is able to fast. And Allah knows best.

Among the Shiite scholars too the above is a popular view.

For instance, in answering a question about long hours of fasting, Mahdī Hadawī

Tahrānī has issued the following verdict:

In the areas that have normal night and day, meaning sun

rises and sets in 24 hours, Muslims need to follow the local times and if they

fall in extreme difficulty in doing this because of the length of the day, then

they are not obliged to fast. They will need to make it up and they can do this

during the short days of winter.

The Dominant View is on the basis of certain observations

from the following verses of the Qur’ān:

وَكُلُوا

وَاشْرَبُوا حَتَّى يَتَبَيَّنَ لَكُمُ الْخَيْطُ الْأَبْيَضُ مِنَ الْخَيْطِ

الْأَسْوَدِ مِنَ الْفَجْرِ ثُمَّ أَتِمُّوا الصِّيَامَ إِلَى اللَّيْلِ

(١٧٨:٢)

And eat and drink until the white thread of the

dawn is totally evident to you from the black thread of night. Then complete the

fast till nightfall. (2:178)

وَ مَن كَانَ

مَرِيضًا أَوْ عَلىَ سَفَرٍ فَعِدَّةٌ مِّنْ أَيَّامٍ أُخَرَ يُرِيدُ اللَّهُ

بِكُمُ الْيُسْرَ وَ لَا يُرِيدُ بِكُمُ الْعُسْر (١٨٧:٢)

And whoever is sick or upon a journey, then (he shall fast) a (like) number

of other days, God desires ease for you, and He does not desire for you

difficulty. (2:187)

These observations are as follows:

- Verse 2:178 makes it clear that fasting from dawn to sunset is a

definite directive.

- Verse 2:187 opens a door that makes it unnecessary to change the

fasting hours. The door is the simple permission to skip the fasting if one is

ill or is in travel.

The conclusion of the Dominant View from the above is that there is

absolutely no way to change the time of fasting and that this is in fact not

needed any way since the person is allowed to skip the fasting (if it is beyond

his tolerance) and to make it up later.

Less Dominant View

In addressing the issue of fasting during long hours, there is another view

that is less popular but no less scholarly. According to this view, Muslims who

live in the areas with extreme length of summer days are allowed to adopt a

shorter daytime on the basis of a city that can be used as a reference point.

In addressing the issue, the Dar al-Iftā al-Misriyyah (Egyptian Centre for

Religious Verdict) has issued the following religious verdict:

يجوز لمسلمي

النرويج وغيرهم ممن شاكلهم في وضعهم إن يصوموا على قدر الساعات التي يصومها أهل مكة

أو المدينة في حال طول نهارهم وقصر ليلهم أو أن يقدروا باقرب البلاد المعتدلة اليهم

وأن يبداوا بالصوم من طلوع الفجر ويفطرون مع ميعاد البلاد التي يقدرون بها من حيث

عدد الساعات ولا يتوقفون على غروب الشمس

It is permitted for Muslims in Norway and others with similar situation to

fast to the length of fasting in Makkah or Madīnah during long days and short

nights or they can adopt the timing of the closest city with moderate (days and

nights) and start their fast from dawn and break it in accordance to the hours

(of fasting) of the city that was taken as the reference and do not need to wait

till sunset.

Similarly, the then head of the centre for Fatwā in Al-Azhar, Muhammad al-Ahmadī

Abū al-Nūr writes:

فنفيد بأن من

يعيش في مثل هذه البلاد التي يطول فيها النهار طولاً بعيداً لا يستطاع معه الصيام

طول النهار، عليه أن يبدأ الصيام من أول طلوع الفجر في البلد الذي يعيش فيه، ويستمر

صيامه ساعات تساوي الساعات التي يصومها من يعيش في مكة المكرمة، ثم يفطر بعد هذه

الساعات

For the person who lives in these cities where the day light is too long that

makes it impossible for him to fast; he needs to start his fasting from the dawn

of the city he lives in and to continue his fasting to the length that is equal

to the length of fasting of one who lives in the glorious Mecca and then to

break his fast after that length.

Among more recent scholars but still in the category of classic traditional

scholars of Islam, Ibn Yūsuf Khalīl

writes:

There are several opinions on the issue, all the obvious result of ijtihād…

Solely on the basis of istihsān, my suggestion is …. that the fasting day be

based on the “earth day” calculation. Based on our research, an average earth

day equates to roughly 12 hours of sunlight, so given this average … a person in

the northern or southern region, taking into consideration the normal

commencement of the work day, etc., could start the fast at approximately 6:00am

and end it at 6:00 pm. …

Similarly among Shiite scholars there are some who have similar religious

view. For example, Mukarram Shīrāzī addresses the issue as follows:

In different books of jurisprudence when there are issues that are related to

abnormal conditions, the view is to follow the norm. … Therefore in areas where

days and nights are longer than the norm one needs to adopt the conditions of a

normal (moderate) place …

It should be noted that all the above quotes are in answering inquiries about

extreme fasting hours within 24 hours.

The Less Dominant View is on the basis of the observation that fasting was

not supposed to be a burden and something that would need to be tolerated.

Fasting was supposed to be a symbolic exercise of patience and taqwā that was

just enough to make the person feel the result of observing God’s directive for

the month of Ramadān and to give him a limited opportunity to smoothly challenge

his desires.

Other than the length of the fast during summer in these countries, it needs

to be appreciated that the issue is not just the difficulty due to the length of

the fasting period in these countries. Some physically strong Muslims may feel

that this is not difficult. Another aspect of the above is whether long fasting

hours are tolerable or not, it certainly does not integrate with typical daily

schedules of people. Looking at the start and the end of fasting during the

winter and summer in the Arabian Peninsula reveals that fasting time was set in

a way that it would nicely fit in with the typical daily schedules of people.

People start fasting shortly before the start of their daily work and they end

the fast around or close to the time when they are resting after a day of

working. This is not the same when people have to break the fast a couple of

hours before the midnight and to start it after having Suhur a couple of hours

passed the midnight.

Therefore according to the Less Dominant View the fact that people “can

survive” when fasting very long hours is not relevant. The simple fact according

to this view is that the fasting time practically meant to be just above half of

the 24 hours for Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula. Fasting for as long as 20 to 23

hours (that is just short of the whole 24 hours) is in a totally different level

of practice and changes the whole mood and the idea behind the act of worship

that is fasting. The Less Dominant View simply refuses to accept that, by

default, the religious duty of people in certain areas of the Earth (who all

happen to be minority Muslims) is to fast more than 80% of the full day. Ibn

Yusuf Khalīl writes:

I realize that there are some Muslims who for whatever reason (be it stamina,

strict adherence to the tradition, etc.) will view my suggestion as heresy and

stick to the dawn and sunset times in their regions regardless of the extremely

long summer days. My recommendation is for those Muslims who concur that Allah

does not want the fast to be overly burdensome on us. And Allah knows best.

Discussion

The Dominant View disagrees with the Less Dominant View based on the

following objections:

a. Changing the time of fasting goes against the explicit instructions

of the Qur’ān in verse 2:178 where the start and the end of the fasting are

clearly mentioned.

b. To suggest changing the time of fasting is in effect questioning the

universality of the instructions of the Qur’ān.

c. Ijtihād is only allowed where shari‘ah is silent, yet here the

Qur’ān is not silent as we are given a clear solution in verse 2:187, where it

says that a person who is ill and a traveller are not expected to fast.

This author argues that from the perspective of the Less Dominant View, all

the three objections can be seen to be unfounded and based on wrong conclusions

from the verses of the Qur’ān:

A. Response to the first objection,

i.e. changing the time of fasting

goes against the explicit instructions of the Qur’ān in verse 2:187.

It is of course a fact that verse 2:178 has explicitly instructed us about

the start and the end of the fasting in a day. The assumption of the objection

is that the start and the finishing points here are the backbone of this

instruction. This, however, is an assumption that can be challenged by looking

at the chart that was given earlier in this article. It is obvious that in the

Arabian Peninsula the instructed start and end points of fasting produce very

smooth and reasonable fasting hours throughout the year. This seems to be

directly associated with the fact that is given at the end of verse 2:187,

emphasizing that God does not want to create difficulties for people. A simple

question can be raised that when the Almighty says He does not want difficulty

for people and wants ease for them, then how it is possible to justify that the

religious duty of Muslims in, for example, Luleå is to fast almost all the day

for several consecutive days (the fact that they are allowed to skip this if

they cannot tolerate it and fast in a different time of the year does not cancel

this question).

We of course know that as the continuation of the mission of the progeny of

Abraham (rta) the Qur’ān had to be revealed in the Middle East and since this

mission was going to be passed to Ishmaelites, therefore the Qur’ān had to be

revealed in the Arabian Peninsula (and of course there can be further reasons

for the choice of this location that we are not aware of and are based on the

ultimate wisdom of the Almighty). However, to bring the issue closer to mind and

for the sake of better understanding, we can carry out a simply mind exercise as

follows:

If the Qur’ān was not revealed in Arabian Peninsula but in Sweden, would dawn

and sunset still have been the start and end of fasting? If this was the case

then (for people who had to fast 23 hours a day when the month of Ramadān was in

summer) how meaningful would the verse: “God does not want difficulty for you

and wants ease for you,” have been? On the other hand, how meaningful would

fasting have been for people who would have to fast only for 6 hours (which is a

routine gap between two meals for many) during the month of December in Luleå

when dawn was around 7:00 AM and sunset was around 1:30 PM?

It is possible based on the above mind exercise to argue that starting the

fast at dawn and ending it at sunset is not the backbone of the instruction of

fasting in the verse 2:178. Rather, it seems that the backbone of the

instruction is the reasonable length of fasting that these two points produce

for the location where the Qur’ān was revealed. Starting and ending the fast

with natural phenomenon like dawn and sunset which also coordinates with prayer

times is of course a blessing and is certainly one of the wisdoms behind the

given instructions in the Qur’ān. However, based on the aforementioned

understanding, this blessing does not allow one to break the backbone of the

divine instruction, which is the reasonable length of fasting.

If we appreciate the above, then we can understand why the Less Dominant View

does not agree this view goes against the Qur’ān.

There is another way of addressing this objection as well which might be more

acceptable by those who are more interested in the exact wording of the verse

2:178.

The concept of “earth day” as quoted from Ibn Yūsuf Khalīl points to the fact

that no matter when the sun rises and when it sets, for human beings, the

routine of day and night activities are mostly unchanged. For example whether

darkness starts at 4:00 PM or 11:00 PM, for a human being with a normal daily

routine, the time of having dinner and sleeping is the same.

It is interesting that verse 2:178, while referring to the start of the time

of fasting in a very technical way,

refers to the time of ending of fast in a less technical way.

In line with the concept of the ‘earth day’ one may argue that “night” in this

verse does not refer to what is known as scientific night, but simply means

“night” in the way that is commonly used by people. For example when a person in

Luleå during the summer time says: “I will visit you tomorrow night”, under

normal circumstances no one interpret that to mean he wants to visit around

11:00 PM. Rather, people normally interpret that in a common sense (in line with

the concept of the “earth day”). If we agree that this is how people commonly

refer to “night” in their everyday usage of the word, then we may well argue

that the same definition of “night” should be applied for the end of the fasting

time.

Again, based on this alternative response, the Less Dominant view does not

change the wording of the Qur’ān, but in fact seeks the intended meaning based

on the understanding that many of the Qur’ānic expressions do not refer to a

technical/scientific meaning of the expressions, but the common sense meaning of

them.

B. Response to the second objection,

suggestion to change the timing of

fasting means questioning the universality of the Qur’ān.

Interestingly enough, it seems easier for the Less Dominant View to defend

the universality of the Qur’ān and it seems like the Dominant View might have

problems fully defending this.

The Dominant View agrees with the Less Dominant View that in places far North

where the length of day is more than 24 hours, the time of Makkah or a city with

normal day and night conditions need to be adopted. However, if (as the Dominant

View argues) the start and the end of fasting, as mentioned in the Qur’ān, is

included among the universal directives of the Qur’ān then one may ask why was

the directive not given in a way that it could apply to all places on the face

of Earth. The Dominant View holds that the start and end points of fasting (as

instructed in the Qur’ān) are universal, yet uses another criterion for places

with more than 24 hours of sunlight. This seems like a contradiction.

For the Less Dominant View, however, this contradiction does not apply. To

them the universal element of the verse of the Qur’ān is not the start and end

points of fasting, but is in fact the length of fasting that result from the

start and end points in the Arabian Peninsula.

In other words, the Less Dominant View has an understanding from verse 2:178

that supports the universality of the directives of the Qur’ān while the

Dominant View holds an understanding that practically conflicts with the

principle of universality of the Qur’ān.

C. Response to the third objection,

i.e. Ijtihād is only allowed where

sharī‘ah is silent and here (with verse 2:187) sharī‘ah is not silent.

According to the Dominant View, since verse 2:187 has opened a way for those

who due to illness or travel may find fasting difficult, therefore it is not

correct to say that sharī‘ah is silent about the issues like long hours of

fasting. It seems like the Dominant View considers the allowance given in verse

2:187 to be relevant to the long hour of fasting as well. For example Shehzad

Saleeem writes on the basis of the same understanding:

Traveling and sickness understandably incapacitate a person. The relief given

is for this reason. Analogously all situations which incapacitate a person can

also be subsumed under this concession given. Hence we can conclude on the basis

of analogical deduction that if a person finds it difficult to fast in a

particular Ramadān because of extreme timings or extreme weather conditions, he

can defer his fasts to some other part of the year when these timings or weather

become manageable for him or her.

The assumption of the Dominant View, which can also be derived from the above

quote, is that obligation (taklīf) is to fast from dawn to sunset, irrespective

of the length of the day. The Dominant View then considers those who cannot fast

during this time to be exceptions and therefore applies the allowance given in

2:187 to these exceptions.

Both the assumption and the application seem to be questionable from the

perspective of the Less Dominant View:

First, as discussed in response to objection “A”, this assumption is not

shared by the Less Dominant View. From the perspective of the Less Dominant View

the backbone of the directive is the length of the fasting rather than the start

and the end point of the fasting. Instead of repeating the reasoning that was

provided earlier, I would like to quote from the late Mahmud Shaltut, the famous

scholar of al-Azhar, with regard to the long fasting hours:

صيام ثلاث

وعشرين ساعة من أصل أربع وعشرين تكليف تأباه الحكمة من أحكم الحاكمين، والرحمة من

أرحم الراحمين

Fasting for 23 hours of 24 hours is an (assumed) obligation that is against

the wisdom of the Best Judge of Judges and the mercy of the Most Merciful of

Merciful Ones.

Second, it needs to be appreciated that verse 2:187 is in fact silent about

the issue of extreme time of fasting. It is the Dominant View that “interprets”

the verse and “analyses” it to apply it to this new issue. It is therefore not

correct to say that the Qur’ān is NOT silent about this issue. The Dominant View

itself has done ijtihād by applying the allowance in verse 2:187 to this

contemporary issue. It is ironic that it then criticizes the Less Dominant View

on the basis of the argument that ijtihād is not needed when the Qur’ān is not

silent.

Third, the analysis of the Dominant View is that since traveling and sickness

to some extent incapacitate a person therefore the relief given in verse 2:187

is because of this. Analogously they then conclude that all situations which

incapacitate a person to the same extent can also be subsumed under the

concession given. There seems to be an illogical analogy here in that verse

2:187 is giving permission for exceptional cases where it is solely the specific

situation of individuals (illness, travel), initiated in/by them, that makes it

difficult for them to fast. However the issue of fasting long hours is not about

specific situation of individuals initiated by/in them. Here it is the

“Directive” (as advised by the Dominant View) not the “Individual’s Situation”

that has caused the issue. This tiny yet important difference makes the analogy

less than flawless.

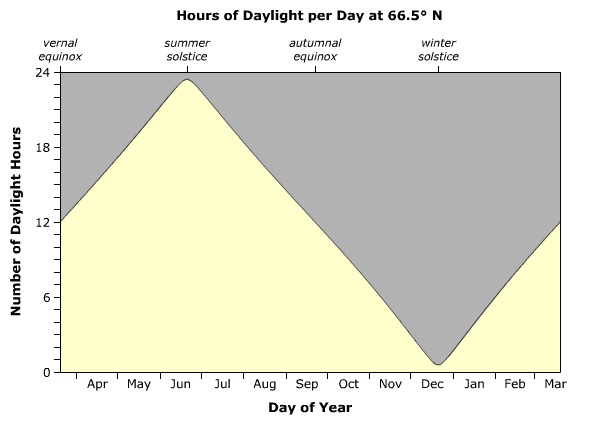

A theoretical argument in favour of the Less Dominant View

The Less Dominant View can also challenge the Dominant view by raising a

theoretical question. Looking at the following graph, it is clear that for areas

at 66.6 latitude the daylight during June will be only a few minutes less than

24 hours.

Whether in those areas there are any residents or not is not relevant. The

question is, since theoretically Muslims can face this situation, where exactly

the Dominant View draws the line.

Source: University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Does the dominant view advise that even if there are only 2 minutes to break

the fast and start the fast again, Muslims in these areas should keep fasting

according to sun dawn and sunset? This does not seem to be a practical advice.

Surely even the Dominant View needs to accept the adjustment of fasting hours

when the fasting time is getting extremely close to 24 hours.

If the above can be appreciated, then there does not seem to be much

difference between the Dominant View and the Less Dominant View. The difference

will only be about where to draw the line, otherwise, theoretically both agree

that at some point (within 24 hours day and night) the fasting time needs to be

adjusted.

Objections of the followers of the Dominant View

Some of the Muslims who strictly prefer the Dominant View have raised

objections as well. Although these objections cannot be considered as academic

ones yet they raise important issues and need to be addressed. Some of the most

important objections and a brief answer based on the Less Dominant View are as

follows:

a. Many can fast during long summer days so what is the need for the

Less Dominant View?

First, it needs to be appreciated that fasting is not supposed to be a

marathon of not eating and drinking. As discussed above, looking at the length

of fasting in the Arabian Peninsula, and in line with the general spirit of

religious directives, fasting is supposed to be a practice that puts some

pressure on us but does not entirely exhaust our energy. Many can keep fasting

while in travel or while being ill. Yet because of the same principle we are not

expected to fast in these situations.

Second, the issue is not just about whether long fasting hours are tolerable

or not. As discussed above, another point is that fasting time in Arabian

Peninsula fits perfectly with the typical working and resting hours of a person

and is therefore nicely integrated with the normal schedule of people. This is

while extreme fasting hours clash with the normal daily schedule of life.

Third, the Less Dominant View does not forbid fasting for the whole day in

the extremely long days. It only provides an alternative and also a solution for

those who find it difficult or against the spirit of fasting, to fast that long.

b. People fast for extremely long hours during summer but then in a few

years time they will fast for extremely short hours during winter. Does this not

solve the problem by balancing the overall fasting time during years?

The issue is not about overall balance of fasting hours. The issue is simply

about abnormal fasting hours during the summer time in some of the areas in the

world. The fact that the person will do extremely shorter fasting during winters

does not take away the difficulty and abnormality of fasting during the long

summer.

c. If we follow the Less Dominant View then is it not fair to also

adopt the Makkah time when fasting during the winter (when days are very short)?

Fasting in winter where days are extremely short would have been an issue if

the concern was merely to adopt typical fasting hours. This however is not the

concern. The basis of the Less Dominant View is the advice given in the Qur’ān

which runs in every religious directive, that is, God does not want difficulty

for you. On this basis the point of focus and the problem in hand is only the

extreme summer times. We should also appreciate that this is not a case of

entering a business transaction where we need to adopt a ‘fair take and give’

policy with the other side of the business. We are merely servants of the

Almighty. He does not need our acts of worship and certainly does not expect us

to do more on the basis of ijtihād.

Having said this, referring to the above graph, in places and times that

fasting time might get extremely short (theoretically it can be as short as only

a few minutes), there seems to be a reasonable ground to discuss whether longer

hours of fasting need to be adopted.

d. If we open the door for this way of reasoning, then we will get into

the danger of changing many of the rules of sharī‘ah based on newly emerged

issues.

Before addressing the above, it needs to be noted that the scholars who hold

the Less Dominant View are mostly categorized as the traditional and classic

scholars of Islam. The views that were quoted for the Less Dominant View all

come from such category of scholars and sources. These scholars are adherents to

the most traditional understanding of Islam that at points can and has generated

practical issues in some Muslim communities yet they have not changed their

traditional views about those issues. The view of these scholars on the issue of

extreme hour of fasting does not come from any radical way of thinking and is

deeply rooted in their understanding of the traditional knowledge and approach

of understanding Islam.

However the main point is that the above concern is based on a wrong

understanding of the reasoning of the Less Dominant View. The Less Dominant View

is not suggesting changing a religious directive. Rather they argue that a

religious directive has not been understood entirely. They have come to this

understanding due to the emergence of a practical issue that is, fasting for

extreme hours. This is not the first time that realising a practical problem

prompts scholars to reassess their understanding of a religious directive in

order to (not change it but) understand it better. If at any time in future

another newly emerged issue prompts some of the most learned scholars of Islam

to reassess their understanding of a religious directive, then this should be a

reason to be proud about the scholarship of Islam rather than to be worried

about it.

Practical problems of the Less Dominant View

The above rather favourable arguments for the Less Dominant View should not

create a misunderstanding that the author is unaware or unappreciative of some

of the obstacles and practical issues related to the Less Dominant View. Two of

these are as follows:

- Since this is a matter of ijtihād and since the scholars who hold the Less

Dominant View have not attempted to coordinate with each other and reach common

specifications, there are a number of questions that will remain with more than

one answer. From what length of day upwards should we consider adopting the

times of a different city? Which city or what basis should be used as the point

of reference?

How should one adopt the different times?

This subjectivity is of course a natural result of any act of ijtihād, however

in this case the range of possible alternatives seems to be quite wide and the

fact that there has been little attempt to bring some agreement on these issues

makes the problem more complex.

- We are well aware of the suffering of Muslims due to lack of unity. Even in

the acts of worship like fasting we can see examples of this (e.g. Muslims

observe the month of Ramadān and the ‘id on different days while being in the

same geographical area). The Less Dominant View can easily result in yet further

disunity in acts of worship among Muslims, especially considering the above

point.

Conclusion

The first point that needs to be appreciated is that the whole issue of

extreme fasting time in some of the countries in the northern parts of the Earth

and the way to deal with this issue is based on ijtihād (religious opinion).

Accordingly, as long as this ijtihād is done based on religiously acceptable

reasoning no one can and should consider one v to be the exact sharī‘ah and the

other one to be against the sharī‘ah.

Two views were discussed and evaluated in this article. There is a Dominant

View that instructs that Muslims should fast from dawn to sunset irrespective of

the length of fasting (as long there is a day and night within 24 hours) unless

this is beyond their capacity, in which case they need to fast during another

time of the year. In contrast, the Less Dominant View argues that Muslims who

are facing extreme hours of fasting are allowed to adopt the fasting time of a

different city in the world where the hours of fasting are more moderate.

According to the Dominant View, the backbone of the instruction of the Qur’ān

in verse 2:187 is the start and the end point of fasting while according to the

Less Dominant view, the backbone of the instruction is the length of fasting

that is supposed to be moderate.

The Dominant View has a practical advantage in that it gives a specific

solution that is straightforward. Accordingly the person either fasts

irrespective of the length of the fasting or postpones his fast if fasting in

extremely long days is beyond his capability. Also it seems like most people

find themselves more comfortable with this view simply because it is literally

in-line with the wording of the Qur’ān.

On the other hand, it is difficult to digest and justify (on the basis of the

Compassion and the Wisdom of the Almighty) the fact that while all Muslims fast

for a maximum of 15 hours in their countries, there are those who are

religiously obliged to fast as long as 20 - 23 hours a day. This simply negates

the fact that God does not want to impose difficulty on people. To argue that

people can choose to fast later in the year if they find it difficult is not an

answer to the above. The question is not about what these people need to do;

rather the question is: why are these people obliged to undertake such a

difficult religious duty in the first place? The places where these extreme

hours of fasting occur are all in non-Muslim countries. The minority Muslims are

already disadvantaged due to lack of enough social support and lack of a

‘fasting atmosphere’ in these non-Muslim countries. The Dominant View puts them

in further disadvantage by advising them that if they cannot fast during the

extreme hours then they need to fast some other time in the year. This for many

Muslims who live in these areas (especially mostly young and elderly) means that

they have to fast when not even the minority Muslim community would provide

support and inspiration (that is naturally provided during the month of Ramadān).

Further, from the spiritual point of view it is understandable that for many

individuals, fasting during the month of Ramadān is always more desirable than

fasting during another month of the year.

Another methodological problem with the Dominant View is its criticism of the

Less Dominant View by bringing up the principle of universality of the

directives of the Qur’ān. As discussed in this article, in practice, it seems

like it is the Dominant View itself that does not adhere to this principle (when

it comes to fasting time in places where there is no proper day in 24 hours).

On the other hand the Less Dominant View has a conceptual rather than literal

approach to the instruction of the Qur’ān about the time of fasting. The

conclusion that is reached seems to be more in-line with the general spirit of

religious directives and (as explained in the discussion section) it also fits

with the issue of universality of the Qur’ān.

However the Less Dominant View can result in a variety of different standards

when it comes to practice. This is because there is no agreed upon ijtihād,

within the Less Dominant View, on when to adopt the timing of a different place

and what place or point of reference can be chosen for this.

This can contribute to further disunity and perhaps clashes among the Muslim

communities.

Having said that, it also needs to be appreciated that different

understanding of religious directives per se, should not create disunity. In

other words, the problem of disunity is rooted in more in-depth socio-cultural

and political platforms rather than mere different understanding of the

religious directives. The first generations of Muslims too had a different

understanding of religious directives, yet, they were much more united than

Muslims of our era.

It is important to appreciate that God expects us to act in accordance with

an honest understanding of our duties. As long as a religious opinion is

formulated with that honesty by people of knowledge and as long as those who

accept that religious opinion are doing so in the honest pursuit of truth, there

should not be any worries nor any clashes between the adherents of different

religious views. This was surely the way of the first generation of Muslims who

witnessed the Prophet of God (sws). May the Almighty guide us all in following

their path.

_______________

|