IV Analysis of Existing Interpretations

and Narratives

A. Analysis of the Matn

An analysis of the opinion of the

scholars shows that their comments are not available on all the four

representative narratives.

Hence their analysis of the narratives is not comprehensive. However, if in a

nutshell, their opinions are evaluated disregarding this fact, it can be said

that they can be classified into two categories:

i. The narratives refer to memorization

of the Qur’ān by ‘Alī (rta) after the death of the Prophet (sws).

ii. The narratives refer to a written

personal collection made by ‘Alī (rta) after the death of the Prophet (sws).

The first of these options is unlikely

because although the word jama‘ can refer to both memorization of the complete

Qur’ān and to its written collection, there are strong indications in these

narratives that here it has been used for a written collection. Perhaps the

strongest of these indications is that variants from ‘Alī (rta),

Yamān

and from Ibn Sīrīn

(other than the one that contain Ash‘ath) refer to the fact that the collection

made by ‘Alī (rta) was in written form between two covers.

If the narratives refer to a personal

written collection, then the following questions arise on it:

Firstly, some of the variants mention

that ‘Alī (rta) took to this task because additions were being made to the

Qur’ān.

The reaction depicted by Abū Bakr (rta) is contrary to common sense. His

response: “What a good opinion you have formed,” is inappropriate on such a

grave situation. If additions were really being made, how could he have not been

more concerned and taken additional measures to safeguard the Qur’ān? He should

have very naturally inquired about the nature of these additions and about the

people responsible for it. Moreover, if additions were being made to the Book of

God, it seems strange that out of all the people, only one person came to know

of these additions.

Secondly, if ‘Alī (rta) thought that

additions were being made to the Book of God, why is it that he did not take the

initiative to inform other Companions (rta) about such an alarming situation? On

the contrary, narratives say that it is only after he was asked about his delay

in pledging allegiance that he informed them of this.

Thirdly, it is alleged by classical

scholars that it was after the battle of Yamāmah that Abū Bakr (rta) at the

behest of ‘Umar (rta) undertook the collection of the Qur’ān.

It is strange, as pointed out by Schwally also, that at that time no use was

made of this Qur’ān collected by ‘Alī (rta). Moreover, we find Abū Bakr (rta)

displaying two contradictory attitudes. In the narratives under discussion, he

seems very pleased that ‘Alī (rta) is undertaking this task. However, in the

narratives which depict the collection of the Qur’ān after the battle of Yamāmah,

we find him very hesitant in attempting the task of collection.

Fourthly, as such, the overall picture

which emerges is very fragmentary and seemingly incomplete. Neither do we find

any report of Abū Bakr (rta) asking ‘Alī (rta) to bring over the collected

Qur’ān nor do we find ‘Alī (rta) bringing it over to him at his own initiative.

It seems that the whole endeavour had no further role in Muslim history, though

common sense demands that this should not have been the case.

Fifthly, as Ibn Hajar has pointed out,

‘Alī (rta) himself has specified that it was Abū Bakr (rta) who was the first to

collect the Qur’ān between two covers:

حدثنا عبد الله قال حدثنا يعقوب بن سفيان قال : حدثنا أبو نعيم

قال : حدثنا سفيان ، عن السدي ، عن عبد خير ، عن علي رضي الله عنه قال : رحم الله

أبا بكر هو أول من جمع بين اللوحين

‘Abd Khayr reports that ‘Alī (rta)

said: “May God have mercy on Abū Bakr; he was the first to collect [the Qur’ān]

between two covers.”

As a result, we have two contradictory

reports about the first collection of the Qur’ān between two covers.

Sixthly, there is no narrative in the

six canonical books of Hadīth regarding any collection made by ‘Alī (rta) in

spite of the fact that they contain chapters which record narratives on the

collections made by the first three caliphs. As pointed out by Schwally, it is

only tafsīr or history books which have been influenced by Shiism that mention

such narratives.

Seventhly, some variants

of the narratives speak of a chronological collection. What exactly was the

purpose of arranging the Qur’ān chronologically. Had it been of any

significance, would not have the Prophet (sws) done so?

Moreover, the ascription of such a

collection to ‘Alī (rta) is also not very sound. There is nothing reported from

‘Alī (rta) himself about the nature of arrangement in which he compiled the

Qur’ān. It is only later people like ‘Ikramah or Muhammad ibn Sīrīn who report

that this collection was chronological.

In the narrative from ‘Ikramah quoted

above, the endeavour of this chronological collection is in fact attributed to a

group of people. The words are: “Did they compile the Qur’ān according to its

sequence of revelation?” (ألفوه كما أنزل ، الأول

فالأول); the words are not: “Did he compile the Qur’ān

according to its sequence of revelation?” (ألفه كما

أنزل ، الأول فالأول).

In the following narrative from Muhammad

ibn Sīrīn, an unidentified narrator says: “People reckoned that ‘Alī had written

it in the chronological order” (فزعموا أنه كتبه على

تنزيله). The word فزعموا

has an obvious ring of vagueness around it.

أخبرنا إسماعيل بن إبراهيم عن أيوب وابن عون عن محمد قال نبئت

أن عليا أبطأ عن بيعة أبي بكر فلقيه أبو بكر فقال أكرهت إمارتي فقال لا ولكنني آليت

بيمين أن لا أرتدي بردائي إلا إلى الصلاة حتى أجمع القرآن قال فزعموا أنه كتبه على

تنزيله قال محمد فلو أصيب ذلك الكتاب كان فيه علم قال بن عون فسألت عكرمة عن ذلك

الكتاب فلم يعرفه

Muhammad ibn Sīrīn said: “I have been

told that ‘Alī delayed pledging allegiance to Abū Bakr. So Abū Bakr met him and

said: ‘Are you averse to pledging allegiance to me?’ He replied: ‘By God! The

truth is that I had sworn not to wear my cloak except for the Friday prayers

until I have collected the Qur’ān.’” One of the narrators said: “People reckoned

that ‘Alī had written it in the chronological order.” Muhammad ibn Sīrīn said:

“If that book is obtained it would have a lot of knowledge.” Ibn ‘Awn said: “I

asked ‘Ikramah about it and he did not know of any such book.”

A possible answer to some of the

questions raised above is that they are a classic case of argumentum

e silentio: Perhaps Abū Bakr (rta) did

express this concern and perhaps others besides ‘Alī (rta) were aware of

additions being made in the Book of God and perhaps the collection made by ‘Alī

(rta) did have some role in the collection made later by Abū Bakr (rta) but all

this has not been reported, as is the case with many historical incidents.

The response to this critique is as

follows: If the nature of an incident is such that if it ever happened, then

common sense demands that it should have been reported and that a report of

silence would be considered improbable and unlikely, then it cannot be regarded

as a case of such a fallacy.

The cited critique of the scholars on

the arrangement of the mushaf reported by al-Ya‘qūbī is strong.

B. Analysis of the Isnād

As referred to earlier, these narratives

are reported from the following four persons.

i. ‘Alī (rta)

ii. Al-Yamān

iii. ‘Ikramah, mawlā of Ibn ‘Abbās (rta)

iv. Muhammad ibn

Sīrīn

Our traditional scholars have referred

to the inqitā‘ in the chain of narrations. It is evident that this inqitā‘ is

obvious in the case of Ibn Sīrīn’s Narratives. However, it needs to be examined

in the case of ‘Ikramah’s narratives. While, this inqitā‘ is obviously not

present in the case of narratives of ‘Alī (rta). No information is available on

the identity of al-Yamān as will be shown later.

I will now analyze these chains.

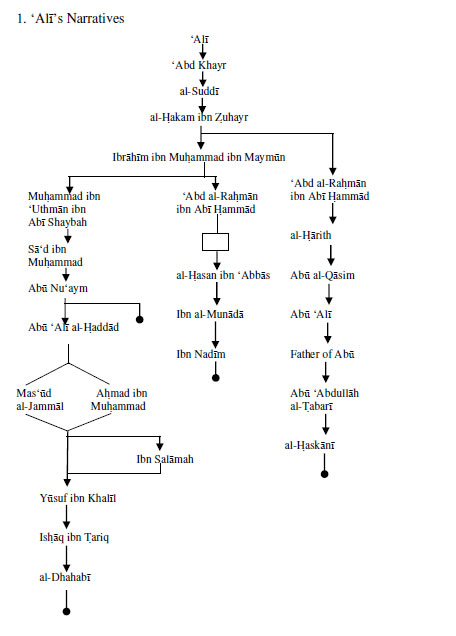

The following charts reflect the chains

of the narratives reported by these three narrators:

1. ‘Alī’s Narratives

Observations

i. In the

above chain, al-Hakam ibn Zuhayr is suspect. Yahyā ibn Ma‘īn

has said about him: laysa hadīthuhū bi shay’. ‘Abd al-Rahmān reports that

his father Abū Hātim

has called him matrūk al-hadīth, lā yuktabu hadīthuhū. Abū Zur‘ah

says that he is wāhī al-hadīth. Al-Nasā’ī also regards him to be

matrūk al-hadīth.

Al-Bukhārī

says that he is munkar al-hadīth; Ibn Hajar

has referred to him as matrūk.

ii. Ibrāhīm

ibn Muhammad ibn Maymūn has been mentioned by Asadī among the du‘afā’ and

said that he is munkar al-hadīth.

iii. In the chain recorded by Ibn

Nadīm, there is a missing person (indicated by a blank box in the chart above)

between al-Hasan ibn ‘Abbās and ‘Abd al-Rahmān ibn Abī Hammād. This is evident

from the words of the former who says: ukhbirtu ‘an ‘Abd al-Rahmān ibn Abī Hammād

(I have been informed by ‘Abd al-Rahmān ibn Abī Hammād

through someone).

iv. Muhammad ibn ‘Uthmān ibn Abī Shaybah is suspect in the eyes of some

authorities. Ibn Hajar

records that according to ‘Abdullāh ibn Ahmad ibn Hanbal he is a liar and Ibn

Khirāsh says that he fabricates narratives.

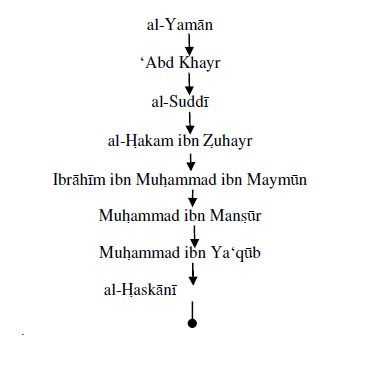

2. Al-Yamān’s Narrative

Observations

i. Al-Yamān is a majhūl

person. No authority has specified that ‘Abd Khayr narrates from such a person.

‘Abd Khayr himself is a companion of ‘Alī (rta). One possibility is a tashīf.

‘Abd Khayr ibn Yazīd was erroneously written as ‘Abd Khayr ‘an al-Yamān.

[(عبد

خيربن يزيد) as (عبد

خير عن اليمان)].

ii. The jarh on al-Hakam ibn

Zuhayr and Ibrāhīm ibn Muhammad ibn Maymūn has already been pointed out.

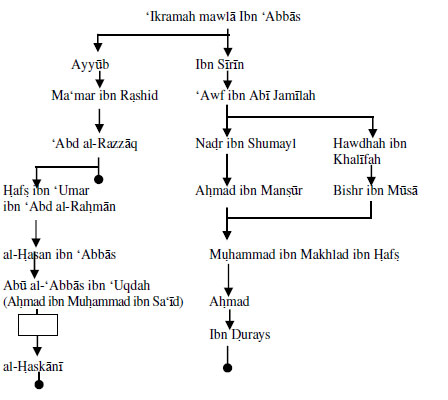

3. ‘Ikramah’ Narratives

Observations

i. ‘Ikramah died in 107 AH at the age of 84. Hence he was born in 23 AH.

This means that he was not a witness to the event reported in the narrative,

which thus must also be regarded as munqati‘.

He could have heard this narrative from ‘Alī (rta). However, Abū Zur‘ah

says that his narratives from ‘Alī (rta). are mursal. So one cannot even

be certain that he has heard this narrative from ‘Alī (rta).

We also find the following jarh on him:

حدثنا الحسن بن علي ومحمد بن أيوب قالا حدثنا يحيى بن المغيرة قال حدثنا جرير عن

يزيد بن زياد عن عبد الله بن الحارث قال دخلت على علي بن عبد الله بن عباس فإذا

عكرمة في وثاق عند باب الحسن فقلت له ألا تتقي الله قال فإن هذا الخبيث يكذب على

أبي

‘Abdullāh ibn al-Hārith said: “I came to ‘Alī ibn ‘Abdullāh ibn ‘Abbās and found

that ‘Ikramah was chained near the door of Hasan. I said to him: ‘Do you not

fear God.’ He replied: ‘This hideous person fabricates lies about my father.’”

ii. Though the muhaddithūn have generally regarded ‘Awf ibn Abī Jamīlah

to be a trustworthy person, here is some contrary evidence to

his trustworthiness:

Abū Zur‘ah and al-‘Uqaylī have mentioned him in their respective books both

titled al-Du‘afā’.

Al-Hākim records:

قلت فعوف بن أبي جميلة قال ليس بذاك

I asked: “[What about] ‘Awf ibn Abī

Jamīlah?” He [al-Dāraqutnī]

replied: “laysa bi dhaka.”

Al-Juzjānī records:

عوف بن أبي جميلة الأعرابي يتناول

بيمينه ويساره من رأي البصرة والكوفة

‘Awf ibn Abī Jamīlah al-A‘rābī

would [carelessly] accept narratives from his right and left from the opinion of

the [people of] Basrah and Kūfah.

Al-Mizzī records:

قال بعضهم يرفع أمره إنه ليجيء عن الحسن بشيء ما يجيء به أحد

Some of them are of the opinion

that he is not trustworthy. He narrates from al-Hasan what no one else ever has.

About Hawdhah ibn Khalīfah, al-Mizzī

records that in the opinion of Yahyā ibn Ma‘īn he is da‘īf in what he

narrates from ‘Awf.

iii. In the opinion of Abū Hātim, Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid makes mistakes in what he

has narrated whilst residing in Basrah

and we know that Ayyūb ibn Abī Tamīmah al-Sakhtiyānī is a Basran.

iv.

Halbī in his Kashf al-Hathīth records about Abū al-‘Abbās ibn ‘Uqdah

(Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Sa‘īd):

Some regard him to be da‘īf and others as reliable (da‘‘afahu ghayru

wāhidin wa qawwāhu ākharūn). According to al-Dhahabī, he would not fabricate

narratives but would narrate gharā’ib and manākīr and narrate a

lot from unknown people (kathīr al-riwāyah ‘an al-majāhīl).

v.

There is an unspecified narrator between al-Haskānī and al-Hasan ibn ‘Abbās

rendering this variant as broken (munqati‘).

vi.

Al-Hasan ibn ‘Abbās is regarded as extremely weak by both Sunnī and Shiite

works. In fact, Ibn Hajar has quoted al-Najāshī’s jarh on him:

وقال هو ضعيف جدا له كتاب في فضل انا أنزلناه في ليلة القدر وهو ردئ الحديث مضطرب

الألفاظ لا يوثق به وقال علي بن الحكم ضعيف لا يوثق بحديثه وقيل انه كان يضع الحديث

And he [--Ibn Najāshi --]

has called him da‘īfun jiddan. He has a book on the blessings of Sūrah

Qadr which has inauthentic narratives, discrepancies in its words and cannot be

relied upon. And ‘Alī ibn al-Hakam said: “He is da‘īf and his narratives

cannot be relied upon.” And it is said that he used to fabricate Hadīth.

Al-Najāshī’s words are:

له كتاب: إنا أنزلناه في ليلة القدر و هو كتاب ردّي الحديث مضطرب الألفاظ

He is

da‘īfun jiddan.

He has a book on Sūrah Qadr – a book which has

inauthentic narratives and discrepancies in its words.

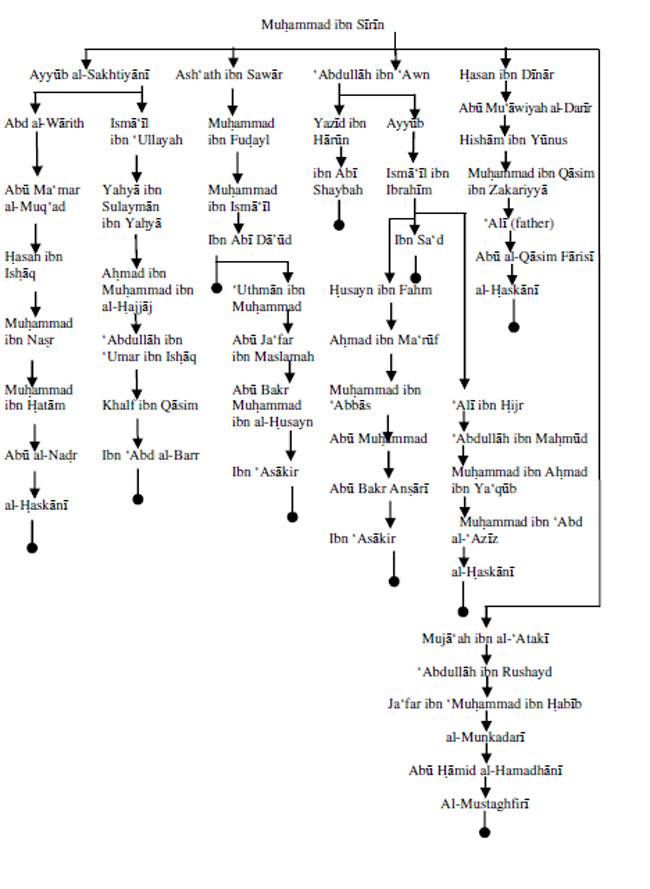

4. Ibn Sīrīn’s Narratives

Observations

As pointed out earlier by Ibn Hajar, there is inqitā‘ in these

narratives.

Now if it is considered that Ibn Sīrīn’s informant was ‘Ikramah, as is the case

with the narratives attributed to ‘Ikramah, even then the issue of inqitā‘

stands as ‘Ikramah was not a witness to the events reported in these narratives,

as pointed out earlier.

_______________________

Nu‘aym Ahmad ibn ‘Abdullāh ibn Ahmad ibn Ishāq ibn Mūsā ibn Mihrān al-Asbahānī,

Hilyah al-awliyā’, 4th ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dār al-kitāb al-‘arabī, 1405 AH), 67; Ibn Nadīm,

Al-Fihrist, 44. Al-Dhahabī, Tadhkirah al-huffāz, vol. 2, 661.

l-Bukhārī, Al-Jāmi‘ al-sahīh, 3rd ed., vol. 4 (Beirut: Da#r Ibn Kathi#r, 1987), 1907, (no. 4701).

ibn Abī Hātim, Al-jarh wa al-ta‘dīl, 1st ed., vol. 3 (Beirut: Dār al-ihyā’ al-turāth al-‘arabī, 1952), 118.

(Halab: Dār al-wa‘y, 1396 AH), 31.

ibn Hajar al-‘Asqalānī, Taqrīb al-tahdhīb, 1st ed. (Syria: Dār al-rashīd, 1986) 175.

ibn Hajar

al-‘Asqalānī, Lisān al-mīzānvol. 1 (Beirut: Mu’assasah al-a‘lamī li al-matbū‘āt, 1986), 107.

Beirut: Dār al-kutub al-‘ilmiyyah, 1959), 82.

|